Current Issue

Quality Evaluation and Bioactive Properties of Sorghum (Sorghum bicolor)-Acha (Digitaria exilis) Cereal Blends Enriched with Cricket (Brachytrupes membranaceus) Protein Derivatives

Anih Peace Ogomegbunam1,*, Ochelle Paul Ohini2, Mbanali Uchenna Ginikanwa3

1Department of Food Science and Technology, Federal University of Agriculture, Makurdi, Benue State, Nigeria

2Department of Food Science and Technology, Federal University, Dutsin-Ma, Katsina, Nigeria

3Federal University of Technology, Owerri. Nigeria

*Corresponding author: Anih Peace Ogomegbunam, Department of Food Science and Technology, Federal University of Agriculture, Makurdi, Benue State, Nigeria, Phone Number: +234 803 293 6159, E-mail: [email protected]

Received Date: November 03, 2025

Publication Date: December 05, 2025

Citation: Ogomegbunam AP, et al. (2025). Quality Evaluation and Bioactive Properties of Sorghum (Sorghum bicolor)-Acha (Digitaria exilis) Cereal Blends Enriched with Cricket (Brachytrupes membranaceus) Protein Derivatives. Nutraceutical Res. 4(2):16.

Copyright: Ogomegbunam AP, et al. © (2025).

ABSTRACT

This study evaluated the bioactive properties of sorghum-acha cereal blends enriched with cricket protein derivatives. Whole cricket meal (WCM), defatted cricket meal (DCM), and cricket protein hydrolysate (CPH) were incorporated (10%) into sorghum-acha flour (80:10). Blends (SAWCM, SADCM, SACPH), analyzed for in vitro antioxidant (DPPH, FRAP, ORAC), antidiabetic (α-amylase/α-glucosidase inhibition) activities, alongside in vivo effects in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. SACPH exhibited superior antioxidant activity (34.9% DPPH, 0.34% superoxide scavenging) compared to sorghum-only control (32.5%, 0.23%). Cricket-enriched blends showed moderate enzyme inhibition (38.5–52.5% α-amylase; 31.5–42.7% α-glucosidase) versus acarbose (90.5%, 85.5%). In vivo, treated rats displayed improved lipid profiles (TC, TG, LDL, HDL) and liver biomarkers (ALT, AST, ALP) versus diabetic controls. Results suggest cricket-fortified blends possess nutraceutical potential to mitigate diabetes, oxidative stress, and liver dysfunction, while addressing malnutrition in resource constrained environment.

Keywords: Antidiabetic, Antioxidants, Functional Properties, Protein Hydrolysates, Sensory Evaluation.

INTRODUCTION

Bioactive compounds are non-nutritional food constituents present in small quantities that exert beneficial physiological and cellular effects beyond basic nutrition. Examples include flavonoids, anthocyanins, tannins, betalains, carotenoids, plant sterols, and glycosylates [1]. Among these, polyphenols, predominantly found in fruits and vegetables, display antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and anti-carcinogenic activities, offering protection against various diseases and metabolic disorders [2]. Such properties have driven interest in developing functional foods that deliver preventive and therapeutic benefits [2].

Edible insects are an emerging source of bioactive compounds. In particular, crickets have been shown to contain antimicrobial peptides that defend against infections and environmental stressors [3]. Beyond these peptides, crickets are nutrient-dense, providing approximately 41% protein, 38% fat, and significant amounts of iron, calcium, and essential amino acids such as tryptophan [4]. Their rich profile of bioactive molecules supports their incorporation into food systems aimed at enhancing health outcomes [4]. Nevertheless, any health claims require validation through standardized assays or human trials.

Because of their high fat content, cricket flours are often defatted using solvents such as hexane to improve shelf life and functional properties [5]. Enzymatic hydrolysis of defatted cricket protein yields peptide-rich hydrolysates, which can increase plasma amino acid levels and support muscle synthesis [6]. Whole cricket meal, defatted flour, and protein hydrolysates have been successfully used to fortify cereal-based foods that are typically low in lysine and tryptophan [5].

Sorghum (Sorghum bicolor) ranks as the fifth most important cereal globally and is valued for its high carbohydrate content and adaptability to arid regions [7]. In Nigeria, sorghum underpins many traditional dishes and also serves medicinal and industrial purposes. However, its protein fraction, about 7–10% of kernel weight, is limited by low levels of lysine and tryptophan, reducing its nutritional quality [8]. Incorporating cricket-derived proteins offers a strategy to address these amino acid gaps and enhance sorghum’s value as a staple food.

Acha, or fonio (Digitaria exilis), is one of West Africa’s oldest cereals but remains underexploited despite its resilience and historical significance [9]. In Nigeria, fonio is recommended for diabetic patients due to its favorable glycemic index [10], and its light texture makes it suitable for gluten-intolerant individuals, infants, and those with compromised health. Fonio’s protein content (around 7%) is notable for high methionine and leucine levels, reportedly exceeding those in egg protein [11]. These attributes position fonio as an excellent candidate for nutritional enrichment of cereal blends.

Both grains and insect flours contain anti-nutritional factors, such as phytates, tannins, phenols, and oxalates, that can inhibit nutrient absorption. Processing techniques (soaking, heat treatment, fermentation) effectively reduce these compounds, improving the bioavailability of nutrients in plant- and animal-based foods [12]. By combining whole cricket meal, defatted cricket flour, and cricket protein hydrolysate with sorghum and fonio, it is possible to develop affordable, high-protein blends with enhanced functional and health-promoting properties.

Moreover, the addition of fonio contributes methionine, which is important for liver function and wound healing [13]. Although prior work has explored cricket-cereal mixtures, few studies have assessed the simultaneous incorporation of multiple cricket derivatives, whole meal, defatted meal, and hydrolysate, into sorghum-fonio blends. This study addresses that gap by formulating flour blends enriched with cricket products and evaluating their nutritional quality, antioxidant activity, enzyme-inhibitory effects, and in vivo bioactivities.

Improving the nutritional profile of cereal-based foods is critical for combating malnutrition and undernutrition, especially in developing regions where animal protein is often inaccessible or expensive [14]. Functional food enrichment with cricket-derived proteins offers a sustainable, locally available solution to protein-energy malnutrition. Additionally, chronic degenerative diseases such as diabetes, obesity, cancer, and cardiovascular disorders are on the rise, underscoring the need for dietary interventions enriched with bioactive compounds [15]. Fortified sorghum-fonio blends may therefore serve dual roles in addressing nutrient deficiencies and providing preventive support against chronic diseases.

Given the growing demand for convenient, quick-cooking, ready-to-eat products, developing high-quality, fortified cereal blends aligns with consumer trends and public health goals [16]. By evaluating the quality and bioactive properties of sorghum-fonio blends enriched with whole cricket meal, defatted cricket flour, cricket protein hydrolysate, and carrot flour, this research contributed novel formulations that are both nutritious and functional.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Source of Materials and Experimental Animal Model

Sorghum (Sorghum bicolor) and acha (Digitaria exilis) grains were purchased from Modern Market, Makurdi, Benue State, Nigeria, and live edible crickets (Acheta domesticus) were sourced from Agasha along Gboko Road, Benue State. Twenty‑four (24) healthy, three‑week‑old male Wistar albino rats (100–130 g) were obtained from the National Veterinary Research Institute, Vom, Jos, Plateau State, Nigeria. The rats were housed in well‑ventilated cages in the Department of Home Science and Management, Federal University of Agriculture, Makurdi, with ad libitum access to standard feed and water. Following a seven‑day acclimatization period, they were randomly assigned to four groups (n = 6 per group) and identified by indelible tail, head, and back marks.

Sample Preparation

Preparation of Malted Sorghum Flour

The method described by Marston K, et al. [17] was used with slight modifications for the production of sorghum flour. Sorghum grains were sorted to remove debris, soaked in water for 48 hours, and then drained. The soaked grains were germinated (sprouted) at ambient temperature, followed by sun-drying for another 48 hours. The dried malted grains were milled using a hammer mill and sieved through a 0.5 µm mesh to obtain malted sorghum flour.

Preparation of Acha Flour

The method described by Ayo J, et al. [18] was used for the production of Acha flour. Acha grains were cleaned by winnowing to remove chaff, then washed thoroughly. The grains were sun-dried for 48 hours, milled using a hammer mill, and sieved through a 0.5 µm mesh to obtain acha flour.

Preparation of Cricket Derivatives

The method described by Agarwal JD, et al. [19] was used with slight modifications for the production of the cricket derivatives. Live edible crickets were de-winged, eviscerated, and oven-dried at 60 °C to constant weight. The dried crickets were then milled into a fine powder using a hammer mill to obtain whole cricket meal (WCM). The WCM was defatted using n-hexane in a ratio of 1:3 (w/v) by stirring continuously for 8 hours at room temperature. The mixture was filtered, and the residue, that is defatted cricket meal (DCM), was air-dried under a fume hood to remove residual solvent. The DCM subsequently underwent a two-step enzymatic hydrolysis process. First, it was hydrolyzed with pepsin (pH 2.0) at 37 °C, followed by a second hydrolysis using pancreatin (pH 7.5) at 37 °C. The resulting hydrolysate was centrifuged at 4,000 rpm for 15 minutes, and the supernatant was collected and lyophilized to obtain cricket protein hydrolysate (CPH). Composite blends were formulated using malted sorghum flour, acha flour, and the cricket derivatives (whole cricket meal, defatted cricket meal, and cricket protein hydrolysate) as shown in Table 1.

Table 1. Blend formulation for the production of sorghum-acha flour blends enriched with different cricket derivatives

|

Samples (% w/w) |

Sorghum flour |

Acha flour |

Cricket derivatives |

|

SOF |

100 |

0 |

0 |

|

SAWCM |

80 |

10 |

10 |

|

SADCM |

80 |

10 |

10 |

|

SACPH |

80 |

10 |

10 |

Key: SOF: 100% Sorghum Flour; SAWCM: Sorghum + Acha + Whole Cricket Meal; SADCM: Sorghum + Acha + Defatted Cricket Meal; SACPH: Sorghum + Acha + Cricket Protein Hydrolysate

Pap Preparation

The method described by Banwo K, et al. [20] was used for the production of the pap. To produce the pap, malted sorghum flour (80 g), acha flour (10 g), and different cricket derivatives (10 g), either whole cricket meal, defatted cricket meal, or cricket protein hydrolysate, were thoroughly mixed with water in a ratio of 8:1:1 (flour:water:cricket derivative). The mixture was then cooked at 100 °C for 5 mins with continuous stirring to ensure uniform gelatinization and prevent lump formation. The resulting product was a smooth, nutrient-enriched pap suitable for analysis.

In vitro Antioxidant Properties of Sorghum–Acha–Cricket Extended Flours

1,1-diphenylpicrylhydrazine (DPPH) Radical Scavenging Activity (DRSA)

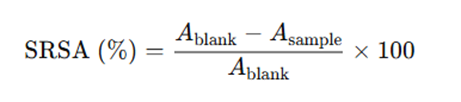

DRSA was determined using the method described by Girgih AT, et al. [21] with slight modifications. The antioxidant activity of protein isolates and hydrolysates was assessed using the DPPH radical scavenging assay for 96-well microplates. Each sample (10 mg/mL) was dissolved in 0.1 M sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.0) containing 1% Triton-X. DPPH was prepared in 95% methanol at 100 µM. Equal volumes (100 µL) of sample and DPPH solution were mixed and incubated in the dark at room temperature for 30 minutes. Absorbance was measured at 517 nm using a spectrophotometer. Glutathione (GSH) served as a positive control. Scavenging activity (%) was calculated as: DRSA (%) = [(A₁ − A₂)/A₁] × 100

Where A₁ is the absorbance of the blank and A₂ is the absorbance of the sample. The EC₅₀ (concentration required to scavenge 50% of radicals) was derived using nonlinear regression of activity versus concentration.

Ferric Reducing Antioxidant Power (FRAP)

The ferric reducing antioxidant power of the protein isolates, hydrolysates and its fractions were determined using the modified method of Benzie and Devaki [22]. The FRAP reagent, freshly prepared by mixing 300 mM acetate buffer (pH 3.6), 10 mM TPTZ, and 20 mM FeCl₃ in a 5:1:1 ratio, was pre-warmed to 37°C. Each sample (10 mg/mL in distilled water) was reacted with 200 µL FRAP reagent and incubated for a short period. Absorbance was read at 593 nm. Iron (II) sulfate heptahydrate (FeSO₄·7H₂O) was used to generate a standard curve, and results were expressed in mM Fe²⁺ equivalents.

Superoxide Radical Scavenging Activity (SRSA)

The method described by Xie Z, et al. [23] was used to determine SRSA of the protein samples. Superoxide scavenging was measured using the pyrogallol autoxidation method. Samples (0.25–1.5 mg/mL) were dissolved in 50 mM Tris–HCl buffer (pH 8.3) containing 1 mM EDTA. In clear tubes, 80 μL sample was mixed with 80 μL buffer, then 40 μL of 1.5 mM pyrogallol (in 10 mM HCl) was added under darkness. The rate of absorbance increase at 420 nm was recorded immediately at room temperature. Scavenging activity (%) was calculated as:

Oxygen Radical Absorbance Capacity (ORAC)

The procedure was based on a previously reported method with slight modifications [24]. Fluorescein (150 μL) was added to black 96‑well plates, followed by 25 μL of Trolox standards (15–240 μM), sample, or buffer (blank), all in duplicate. After a 3 min incubation at 37 °C, 25 μL AAPH was added to initiate oxidation. Fluorescence (λ_ex = 485 nm; λ_em = 528 nm) was monitored for 35 min. The net area under the decay curve, relative to blank, was used to calculate ORAC values, expressed as mmol Trolox equivalents (TE) per gram of sample.

Trolox Equivalent Antioxidant Capacity (TEAC)

TEAC assay was evaluated following the method first described by Cayres CA, et al. [25]. 10mg of sample were mixed with 160 μL ethanol:water (50:50 v/v), then 1.6 mL ABTS⁺ solution was added. After incubation at 37 °C and 250 rpm for 30 min, samples were centrifuged at 14,000 rpm for 2 min. Absorbance was read at 730 nm. Results were expressed as μmol Trolox equivalents per gram of sample.

α‑Amylase Inhibition

The inhibition a-amylase activity was assayed using soluble starch as substrate according to the procedure described previously by Awosika TO and Aluko RE [26] with slight modifications. α‑Amylase inhibition was evaluated using soluble starch as substrate. Sample solutions (50–225 μg/mL peptide) and α‑amylase (28.6 μg/mL) in 0.02 M sodium phosphate buffer (pH 6.9) with 0.006 M NaCl were pre‑incubated at 25 °C for 10 min. Starch (1 g/100 mL) was added and incubated for 10 min. The reaction was stopped with 200 μL DNSA reagent, boiled for 5 min, cooled, diluted with water, and absorbance measured at 540 nm. Acarbose served as positive control. Inhibition (%) was calculated as:

Where Ac is control absorbance, As sample, and Asb sample blank.

α‑Glucosidase Inhibition

α-glucosidase inhibitory activity was assayed according to previously described by Awosika TO and Aluko RE [26] with slight modifications. Rat intestinal acetone powder (300 mg) was homogenized in 9 mL 0.9% NaCl, centrifuged (12 000 g, 30 min), and supernatant used as enzyme. Samples (5–20 mg/mL peptide) in 0.1 M sodium phosphate buffer (pH 6.9) were mixed with enzyme (8.33 mg/mL) and incubated at 37 °C for 10 min. Then, 100 μL 5 mM p‑nitrophenyl α‑D‑glucopyranoside substrate was added, and absorbance at 405 nm was recorded every 30 s for 30 min at 37 °C. Acarbose was the positive control. Inhibition (%) was calculated as:

Where Ac and Acb are control and control blank absorbances, and As and Asb are sample and sample blank absorbances.

Sensory Analysis of Pap

A sensory evaluation of the pap formulations was conducted using a 30-member panel of Food Science and Technology staff and students. Freshly prepared samples were assessed for appearance, mouthfeel, consistency, taste, aroma, and overall acceptability using a nine-point hedonic scale (1 = “dislike extremely,” 9 = “like extremely”) [27]. Panelists cleaned their palates with water between samples, and mean scores for each attribute were calculated to compare the influence of different cricket-derived enrichments on sensory quality.

Induction of Experimental Diabetes and Animal Treatment

Experimental diabetes was induced in Wistar rats. After a 24-hour fast, the rats (n = 24) received a single intraperitoneal injection of streptozotocin (130 mg/kg body weight) and were monitored for 72 hours. Fasting blood glucose (FBG) was measured from tail vein blood using a digital glucometer; rats with FBG >200 mg/dL were considered diabetic. Body weight was recorded before feeding commenced and then weekly for 21 days using an electronic scale. Diabetic rats were randomly assigned to four dietary groups and fed formulated blends containing varying proportions of fermented sorghum flour, acha flour, and cricket products, along with premix (5 %), oil + TBHQ (7 %), corn starch (55 %), fibre (12 %), and salt (1 %), as detailed in Table 2. Each rat received 100 g of its respective diet daily for 21 days, with leftover feed collected and weighed the following morning. Water was provided ad libitum throughout the experimental period, and weekly weight gain was computed accordingly.

Feeding Trials with SOF, SAWCM, SADCM, and SACPH Diets

Feeding trials were conducted to evaluate the nutritional quality of sorghum–acha cereal blends enriched with cricket derivatives. Test diets were formulated to contain 10% protein using SOF, SAWCM, SADCM, and SACPH samples, while a basal diet served as control. After a 7-day acclimatization on commercial starter feed, 24 male Wistar rats were randomly assigned to six groups (n = 4/group). Each group received one of the test or control diets for 21 days. Daily feed intake and body weight were recorded to assess growth performance.

Antidiabetic Study

Induction of Diabetes

Induction of diabetes in wistarrats was carried out according to the method described by Oyeleye SI, et al. [28]. The Wistar rats were acclimatized for one week under standard laboratory conditions with ad libitum access to feed and water. Diabetes was induced via intraperitoneal injection of streptozotocin monohydrate (135 mg/kg body weight) dissolved in 0.9% saline. After 72 hours, fasting blood glucose (FBG) was assessed via tail vein sampling using a glucometer. Rats with FBG ≥200 mg/dL were classified diabetic. Baseline FBG was recorded, and feed intake and body weight were monitored every three days during the experiment. Test diets were formulated as shown in Table 2.

Table 2. Blend formulation for experimental rat feeding

|

Ingredients |

Diet group |

||||

|

Growers mash Control |

Sorghum (SO) |

Whole cricket meal (WCM) |

Defatted cricket meal (DCM) |

Cricket Protein Hydrolysate (CPH) |

|

|

Cornstarch |

55.0 |

55.0 |

55.0 |

55.0 |

55.0 |

|

Protein |

20.0 |

P+15.0 |

P+15.0 |

P+15.0 |

P+15.0 |

|

Salt |

1.0 |

1.0 |

1.0 |

1.0 |

1.0 |

|

Soy oil + TBHQ |

7.0 |

7.0 |

7.0 |

7.0 |

7.0 |

|

Fibre |

12.0 |

12.0 |

12.0 |

12.0 |

12.0 |

|

Premix (micronutrients) |

5.0 |

5.0 |

5.0 |

5.0 |

5.0 |

The experimental design consisted of six groups: Group 1 served as the normal control comprising non-diabetic rats fed a basal diet; Group 2 was the negative control made up of streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats also fed the basal diet; Group 3 included diabetic rats treated with a diet based on sorghum-only flour (SOF); Group 4 received a diet formulated with sorghum–acha blend enriched with whole cricket meal (SAWCM); Group 5 consisted of diabetic rats fed a diet containing sorghum–acha blend with defatted cricket meal (SADCM); and Group 6 received a diet made with sorghum–acha blend enriched with cricket protein hydrolysate (SACPH).

Serum Lipid Profile Analysis

The HDL was determined according to the method described by Oboh G, et al. [29]. Blood samples were collected from each rat by tail vein puncture into plain sterilized tubes, cooled, and centrifuged to obtain serum, which was stored at −20 °C until required for biochemical analyses. All serum parameters were assessed using commercial diagnostic kits following the manufacturers’ instructions. Total cholesterol (TC) was determined using TECO diagnostic kits and calculated as:

TC (mg/dL) = (Absorbance of sample / Absorbance of standard) × Concentration of standard

High-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C) was measured using a commercial diagnostic kit. Triglyceride (TG) levels were determined using an enzymatic colorimetric assay based on hydrolysis of triglycerides to glycerol and fatty acids, followed by quantification of glycerol. Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) was then calculated using the Friedewald formula:

LDL-C (mg/dL) = TC – HDL – (TG / 5)

All analyses were conducted in triplicate and statistical significance was determined at p < 0.05 or p < 0.01 where applicable.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 21. Means and standard deviations were computed as appropriate. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was employed to assess significant differences among treatment groups. Where applicable, differences were considered statistically significant at 95% (p < 0.05) and highly significant at 99% (p < 0.01).

RESULTS

Sensory evaluation of pap made from the cereal blends with cricket derivatives

Pap made from sorghum flour only (SOF) was most preferred across all attributes, appearance, mouthfeel, taste, and overall acceptability, compared to cereal blends enriched with cricket derivatives. SOF scored 7.4, 7.7, 6.4, and 7.0 for these attributes respectively, outperforming the cricket-based samples, which recorded lower scores ranging from 5.1 to 6.5. This indicates that the inclusion of cricket products slightly reduced consumer preference. The significant differences observed suggest that while cricket-enriched formulations offer nutritional benefits, they may require further refinement to match the sensory appeal of the traditional SOF pap. Results are summarized in Table 3.

Table 3. Sensory scores of Pap from sorghum-acha cereal flour blends enriched with cricket derivatives

|

Samples |

Parameter |

|||||

|

Appearance |

Aroma |

Mouthfeel |

Consistency |

Taste |

Overall acceptability |

|

|

SOF |

7.4a±1.38 |

6.8a±1.18 |

7.7a±1.00 |

5.8a±1.80 |

6.4a±1.50 |

7.00a±1.33 |

|

SAWCM |

6.5b±1.58 |

6.5a±1.07 |

5.6b±1.49 |

4.8a±2.06 |

5.8a±1.43 |

6.00b±1.41 |

|

SADCM |

5.5b±1.54 |

6.2a±1.46 |

5.1b±1.56 |

4.5a±2.09 |

5.9a±1.22 |

5.95b±1.27 |

|

SACPH |

6.5ab±1.67 |

6.0a±1.37 |

6.1b±1.92 |

5.1a±1.88 |

5.4a±1.57 |

5.8b±1.57 |

Key: SOF = 100 % Sorghum; SAWCM = 80 % Sorghum + 10 % Acha + 10 % whole cricket meal; SADCM = 80 % Sorghum + 10 % Acha + 10 % defatted cricket meal; SACPH = 80 % Sorghum + 10 % Acha + 10 % cricket protein hydrolysate.

In vitro Antioxidant Properties of Sorghum–Acha–Cricket Extended Flours

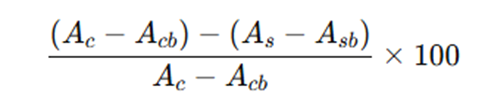

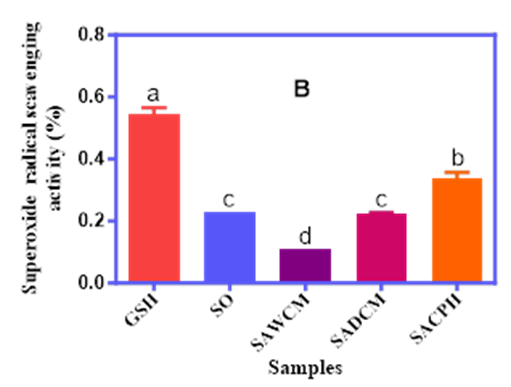

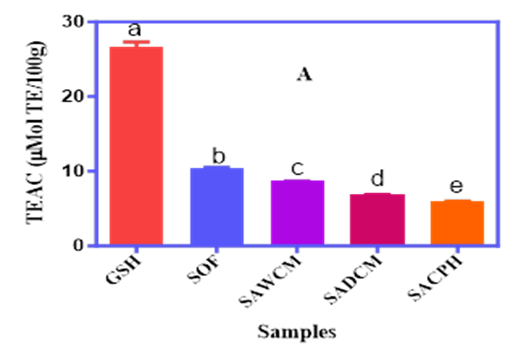

DPPH, SRSA, and FRAP Antioxidant Activities of Fortified Cereal Blends

The antioxidant potential of the fortified cereal blends was evaluated using three complementary assays: DPPH radical scavenging activity (DRSA), superoxide radical scavenging activity (SRSA), and ferric reducing antioxidant power (FRAP), with results presented in Figure 1A–C. The DPPH assay showed that glutathione (GSH) had the highest scavenging activity (53.4%), followed by the SACPH blend (34.9%) and SOF (32.5%), which were not significantly different (p<0.05). SAWCM and SADCM had lower activities of 18.5% and 24.7%, respectively. A clear trend of increasing antioxidant activity was observed with increasing levels of purification from whole meal to hydrolysate, indicating that enzymatic hydrolysis enhances radical scavenging potential.

Similarly, the SRSA values followed a comparable pattern. GSH showed the highest activity (0.55%), while SACPH recorded the highest among the experimental blends (0.34%). The SOF and SADCM blends had comparable and lower values (0.11–0.24%), suggesting that hydrolysate form may offer superior superoxide radical quenching effects due to the release of more bioactive peptides during hydrolysis. The FRAP results revealed reducing capacities between 47.0% and 56.0% for the test samples, while the GSH standard recorded 68.0%. SOF (56%) and SACPH (55%) exhibited the highest ferric reducing activity among the samples, while SAWCM and SADCM showed lower values of 48% and 47%, respectively. These findings collectively suggest that both the composition and processing method of cricket derivatives significantly influence antioxidant performance.

Figure 1A, 1B and 1C. The DPPH Radical Scavenging Activity (A), Superoxide Radical Scavenging Activity (B), and Ferric Reducing Antioxidant Power (C) of Sorghum–Acha Flour Blends Enriched with Whole Cricket Meal (SAWCM), Defatted Cricket Meal (SADCM), and Cricket Protein Hydrolysate (SACPH).

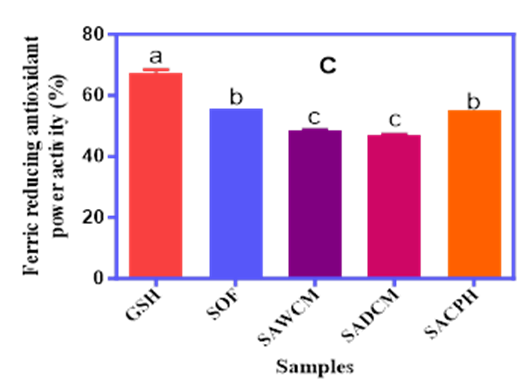

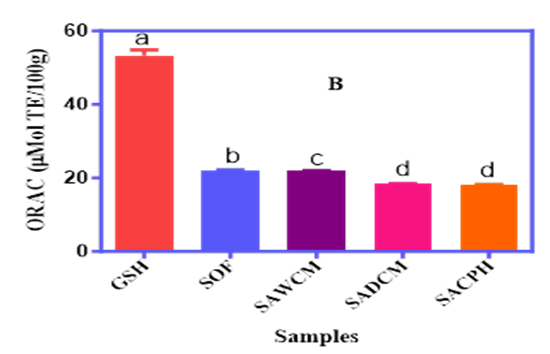

Trolox Equivalent Antioxidant Capacity (TEAC)

The antioxidant potential of sorghum–acha blends fortified with cricket protein derivatives was assessed using Trolox Equivalent Antioxidant Capacity (TEAC) and Oxygen Radical Absorbance Capacity (ORAC) assays, as shown in Figure 2A and 2B. TEAC values ranged from 6.0% to 10.5%, with GSH showing the highest activity (27.5%). SACPH recorded the lowest TEAC (6.0%), significantly (p<0.05) lower than SAWCM and SADCM, suggesting reduced Trolox equivalent activity in the hydrolysate form. ORAC values ranged from 18.2 to 22.2 μMol TE/g, with GSH again highest (53.4 μMol TE/g). SACPH and SADCM had slightly higher ORAC values than SAWCM, indicating better peroxyl radical scavenging. These results highlight how processing and protein form influence antioxidant function in the cereal blends.

Figure 2A and 2B. The TEAC (A) and ORAC (B) Antioxidant Capacities of Sorghum–Acha Flour Blends Enriched with Whole Cricket Meal (SAWCM), Defatted Cricket Meal (SADCM), and Cricket Protein Hydrolysate (SACPH).

α-Amylase and α-Glucosidase Inhibitory Activities of Cereal Blends Fortified with Cricket

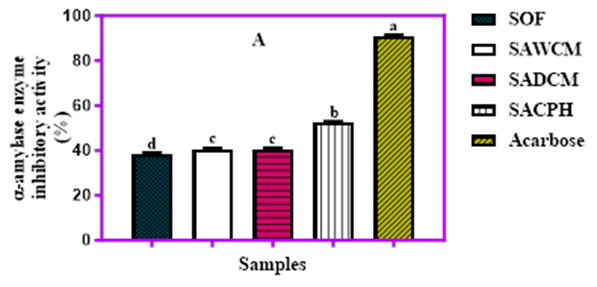

The inhibitory activities of α-amylase and α-glucosidase in cereal blends fortified with cricket protein are presented in Figure 3A and 3B. The α-amylase inhibitory values ranged from 38.5% in the control SOF sample to 52.5% in cricket-extended blends, while the standard drug, acarbose, showed the highest inhibition at 90.7%. All cricket-fortified samples showed significantly (p<0.05) higher α-amylase inhibitory activity than the SOF, with the exception of SAWCM and SADCM, which had statistically similar values. Likewise, the α-glucosidase inhibitory activity followed a similar trend, with the control SOF recording the lowest activity at 31.7% and the standard acarbose reaching 85.5%. The cricket-based blends showed moderate inhibition, ranging from 38.4% to 42.4%, with SAWCM (42.2%) and SACPH (42.4%) displaying the highest values, though not significantly different from each other (p<0.05). Overall, the cricket-enriched cereal blends exhibited enhanced inhibitory potential against both enzymes compared to the SOF control, indicating potential antidiabetic properties.

Figure 3A and 3B. In vitro inhibitory activities of sorghum–acha cereal blends enriched with cricket products against α-amylase (A) and α-glucosidase (B) enzymes.

Key: SOF = Sorghum only (100%), SAWCM = Sorghum 80% + Acha 10% + Whole Cricket Meal 10%, SADCM = Sorghum 80% + Acha 10% + Defatted Cricket Meal 10%, SACPH = Sorghum 80% + Acha 10% + Cricket Protein Hydrolysate 10%.

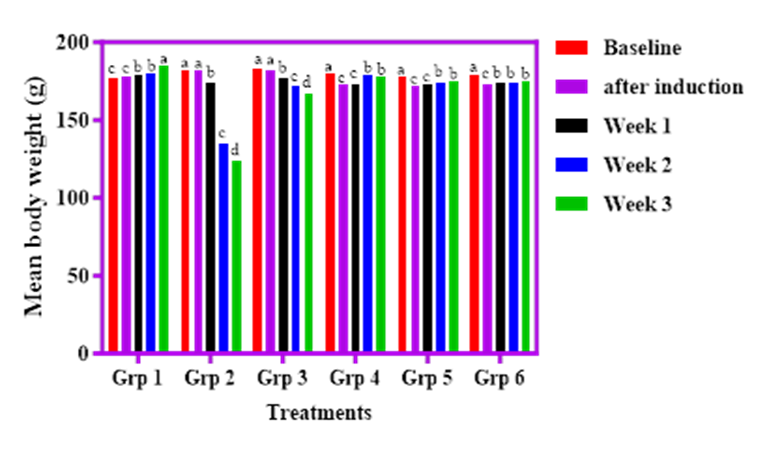

Effect of Cricket Products in Mixed Cereal Pap on Body Weight of STZ-Induced Diabetic Rats

The effect of cricket products on body weight in streptozotocin (STZ)-induced diabetic rats is illustrated in Figure 4. Group 1 rats (normal control) showed a 4.5% increase in mean body weight, rising from 177.0 g at baseline to 185.0 g by week 3. In contrast, Group 2 rats (diabetic control) experienced a significant (p<0.05) weight loss of 31.9%, dropping from 182.0 g to 124.0 g by the third week. Group 3 rats (fed SOF-based diet) recorded a 5.7% weight gain post-induction, which was notably higher than the gain observed in Group 1. Furthermore, Groups 4, 5, and 6, which received cricket-fortified diets (SAWCM, SADCM, and SACPH), exhibited significant (p<0.05) and consistent weight gains throughout the three-week period. These findings suggest that cricket-based cereal diets may mitigate STZ-induced weight loss and support improved weight maintenance in diabetic conditions.

Figure 4. Effect of graded percentages of Sorghum-Acha and cricket meal on body weight of streptozotocin induced diabetic albino rats.

Key: Group1-Normal control; Group 2, STZ control; Group3, 100 % Sorghum;Group 4, STZ + 80 % Sorghum + 10 % Acha + 10 % whole cricket meal; Group5, STZ + 80 % Sorghum +10 % Acha + 10 % defatted cricket meal;Group 6, STZ 80 % Sorghum + 10 % Acha + 10 % cricket protein hydrolysate.

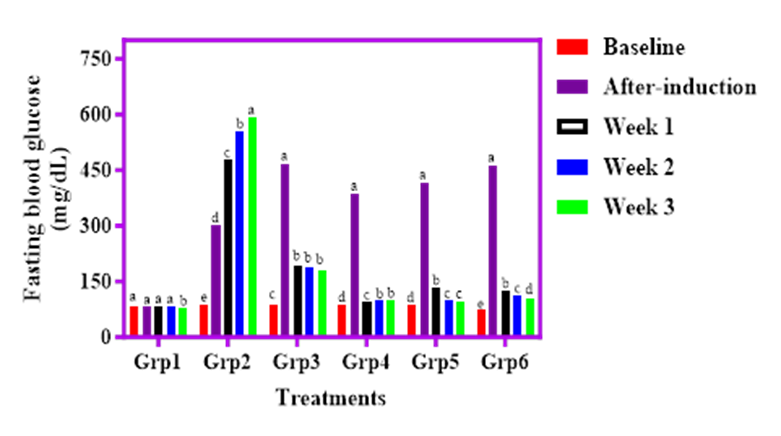

Effect of SOF, SAWCM, SADCM and SACPH Diets on Fasting Blood Sugar

The effect of cricket-fortified cereal diets on fasting blood glucose (FBG) in streptozotocin (STZ)-induced diabetic rats is presented in Figure 5. At baseline, all rat groups had comparable FBG levels, ranging between 73.0 and 88.0 mg/dL. Following STZ induction, a marked elevation in blood glucose levels was observed, with the diabetic control group (Group 2) showing the highest increase to 293.3 mg/dL and progressing to 593.0 mg/dL by week 3. In contrast, the normal control group (Group 1) maintained stable glucose levels (80.0–83.0 mg/dL) throughout the study.

Among the diet-treated groups, rats fed SOF (Group 3) recorded a glucose rise to 466.0 mg/dL post-induction but showed a steady decline to 181.7 mg/dL by week 3. Similarly, Group 4 (SAWCM) rose to 384.7 mg/dL but stabilized around 100.0 mg/dL at week 3. Group 5 (SADCM) and Group 6 (SACPH) also exhibited post-induction spikes to 416.3 mg/dL and 460.3 mg/dL respectively, but improved significantly by week 3 to 97.0 mg/dL and 103.3 mg/dL.

These reductions were statistically significant (p<0.05), indicating that the cricket protein derivatives contributed to glycemic control in diabetic rats. The data suggest that cricket-enriched cereal blends may support the management of diabetes through blood glucose regulation.

Figure 5. Effect of graded percentages of Sorghum, Acha and cricket meal on fasting blood glucose level of streptozotocin induced diabetic albino rats.

Key: Group 1, Normal control; Group 2, STZ control; Group 3, 100 % Sorghum only; Group 4, STZ + 80 % Sorghum + 10 % Acha + 10 % whole cricket meal; Group 5, STZ + 80 % Sorghum + 10 % Acha + 10 % defatted cricket meal; Group 6, STZ + 80 % Sorghum +10 % Acha + 10 % cricket protein hydrolysate.

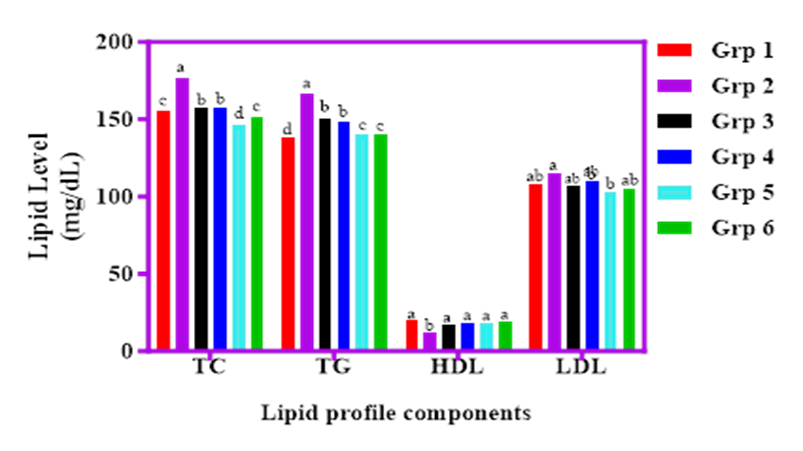

Effect of SOF, SAWCM, SADCM and SACPH on Lipid Profiles

The influence of cricket-based cereal diets on the lipid profiles of STZ-induced diabetic rats is shown in Figure 6. Total cholesterol (TC) was highest in the diabetic control group (Group 2) at 176.5 mg/dL, indicating borderline hypercholesterolemia. In contrast, cricket meal-treated groups recorded moderate TC values: 157.8 mg/dL (SOF), 157.3 mg/dL (SAWCM), 146.5 mg/dL (SADCM), and 151.6 mg/dL (SACPH), all within the normal recommended range (80–200 mg/dL), suggesting a lipid-lowering potential.

Triglyceride (TAG) levels followed a similar trend, with Group 2 showing the highest value (166.6 mg/dL), while the control group (Group 1) had the lowest (138.1 mg/dL). Groups 5 and 6 (SADCM and SACPH) showed no significant difference (p>0.05), with values of 140.3 mg/dL and 140.5 mg/dL respectively. Low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol levels were highest in Group 2 (114.7 mg/dL) and lowest in Group 1 (102.0 mg/dL). Cricket-enriched groups had moderately reduced LDL values (102.6–107.1 mg/dL), demonstrating a protective effect.

High-density lipoprotein (HDL), or "good" cholesterol, was significantly higher (p<0.05) in Group 1 (19.7 mg/dL) and lowest in Group 2 (12.5 mg/dL), with the cricket-fed groups showing improved HDL levels. Overall, cricket-based diets positively influenced lipid profiles, suggesting potential benefits in managing dyslipidemia associated with diabetes.

Figure 6. Effect of graded percentages of Sorghum, Acha and cricket meal on lipid profile level of streptozotocin induced diabetic albino rats.

Key: Group 1, Normal control; Group 2, STZ control; Group 3, 100 % Sorghum only; Group 4, STZ + 80 % Sorghum + 10 % Acha + 10 % whole cricket meal; Group 5, STZ + 80 % Sorghum + 10 % Acha + 10 % defatted cricket meal; Group 6, STZ + 80 % Sorghum + 10 % Acha + 10 % cricket protein hydrolysate.

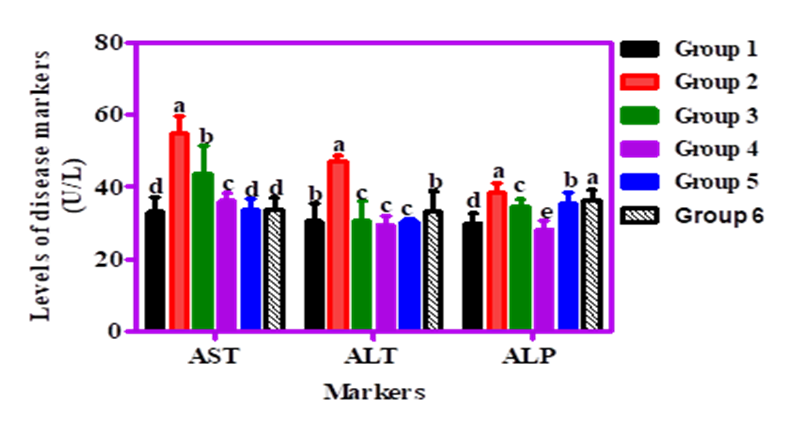

Impact of SOF, SAWCM, SADCM and SACPH on Liver Function Markers

Figure 7 illustrates the effect of cricket-enriched diets on liver function markers in STZ-induced diabetic rats. Alanine aminotransferase (ALT) levels significantly (p<0.05) decreased in treated groups, ranging from 33.2 to 29.5 U/L. Alkaline phosphatase (ALP) levels also reduced significantly (p<0.05) from 38.5 U/L in the diabetic group to 36.5–28.2 U/L in the treated groups. Similarly, aspartate aminotransferase (AST) levels dropped significantly (p<0.05) from 54.8 U/L (Group 2) to 43.8–33.8 U/L across cricket-fed groups. These reductions indicate that cricket-based diets mitigated liver damage in diabetic rats, with biomarker levels returning closer to those of non-diabetic controls. Overall, the cricket protein-enriched diets showed hepatoprotective potential in managing liver dysfunction associated with diabetes.

Figure 7. Effect of graded percentages of Sorghum, Acha, and cricket-derived products on liver function markers (ALT, AST, and ALP) in streptozotocin-induced diabetic albino rats.

Key: Group 1 – Normal control; Group 2 – STZ control; Group 3 – 100% Sorghum only; Group 4 – STZ + 80% Sorghum + 10% Acha + 10% Whole cricket meal (SAWCM); Group 5 – STZ + 80% Sorghum + 10% Acha + 10% Defatted cricket meal (SADCM); Group 6 – STZ + 80% Sorghum + 10% Acha + 10% Cricket protein hydrolysate (SACPH).

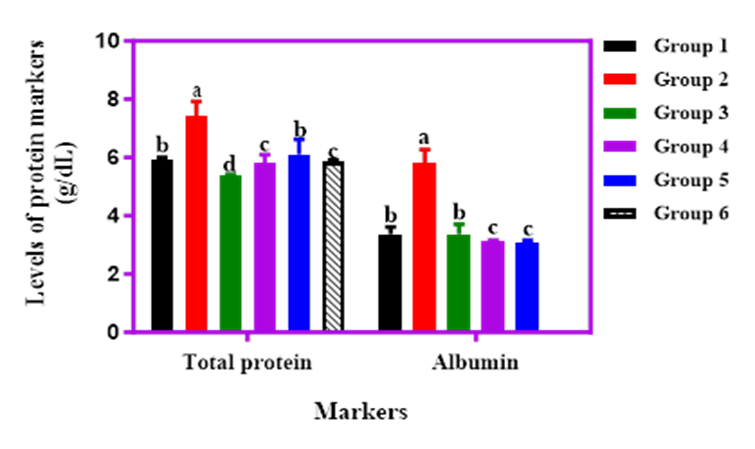

Effect of SOF, SAWCM, SADCM and SACPH Diets on Serum Total Protein and Albumin Levels

Figure 8 illustrates the effect of cricket protein-enriched sorghum-acha blends on serum total protein (TP) and albumin levels in STZ-induced diabetic rats. Albumin, which makes up 50–60% of total serum protein and is synthesized in the liver, is a crucial marker of liver function [30]. Normal albumin levels range from 3.5–5.0 g/dL. In this study, the diabetic control group (Group 2) had the highest TP (7.43 mg/dL) and albumin (4.83 mg/dL) levels. Rats fed cricket-extended diets had TP levels ranging from 5.36 to 6.10 mg/dL, all within the normal range. Group 3 (SOF) recorded the lowest albumin value of 3.10 mg/dL. Overall, cricket protein inclusion did not adversely affect protein metabolism, and the diets appeared to support stable serum protein and albumin concentrations, suggesting potential for use in nutritional formulations aimed at managing diabetes without impairing liver synthetic functions.

Figure 8. Effect of graded percentages of sorghum-acha enriched with cricket products on the total proteinand albumin levels of streptozotocin induced diabetic albino rats.

Key: Group 1: Normal control; Group 2: STZ Control; Group 3: Sorghum 100%, Group 4: STZ + 80% sorghum + 10% Acha + 10% Whole cricket meal; Group 5: STZ + 80% Sorghum + 10% Acha + 10% defatted cricket meal, Group 6: STZ + 80% Sorghum + 10% Acha + 10% cricket protein hydrolysate.

DISCUSSION

This study explored the bioactive properties, enzyme inhibitory activities, and in vivo antidiabetic effects of sorghum-acha flour blends extended with cricket products, including whole cricket meal (SAWCM), defatted cricket meal (SADCM), and cricket protein hydrolysate (SACPH). The results offer significant insights into the potential of these blends as functional foods for managing oxidative stress and diabetes, conditions that pose substantial global health challenges. By combining traditional cereals with an unconventional protein source like cricket, this research bridges nutritional science and sustainable food innovation, providing a foundation for further exploration and application.

The antioxidant capacity of the flour blends was assessed through multiple assays, including DPPH radical scavenging activity (DRSA), superoxide radical scavenging activity (SRSA), ferric reducing antioxidant power (FRAP), Trolox equivalent antioxidant capacity (TEAC), and oxygen radical absorption capacity (ORAC). These assays collectively highlight the blends’ ability to neutralize free radicals and reduce oxidative stress, a critical factor in chronic diseases such as diabetes [31]. The DRSA results, ranging from 18.5% to 34.2%, revealed that the SACPH-extended sample exhibited the highest scavenging activity (34.2%), significantly outperforming SAWCM (18.5%) and SADCM (23.6%). This enhancement is likely due to enzymatic hydrolysis with pepsin and pancreatin, which breaks peptide bonds, releasing free amino acids and bioactive peptides that readily interact with DPPH radicals [32]. Although the standard glutathione (GSH) showed a higher DRSA of 53.2%, the SACPH sample’s performance suggests its potential as a natural antioxidant source, capable of mitigating free radical-mediated damage.

Similarly, the SRSA results underscored the blends’ ability to scavenge superoxide radicals, highly reactive oxygen species implicated in cellular damage and lipid peroxidation [33]. Values ranged from 0.11% (SAWCM) to 0.34% (SACPH), with GSH at 0.55%. The progressive increase from SAWCM to SADCM (0.23%) to SACPH mirrors the DRSA trend, reinforcing the role of hydrolysis in enhancing antioxidant activity. Superoxide radicals, produced during normal physiological processes, can become excessive in chronic conditions, overwhelming endogenous defenses like superoxide dismutase (SOD) [34]. While the blends’ SRSA was lower than GSH, their capacity to augment these defenses through dietary means is promising. Notably, no clear correlation was observed between hydrophobic amino acid content and SRSA, contrasting with findings by Gharibzahedi SMT, et al. [35] on chickpea hydrolysates. This suggests that peptide size, sequence, or other structural factors may be more influential [36], warranting further investigation into the specific bioactive components responsible.

The FRAP assay, which assesses the reduction of ferric ions to ferrous ions as a measure of electron-donating capacity [37], revealed distinct trends in antioxidant potential. Values ranged from 47% in SADCM to 55% in SACPH, with SOF slightly higher at 56%, and GSH peaking at 68%. The cricket-extended blends generally exhibited lower FRAP values than the control, suggesting that cricket incorporation may alter the antioxidant synergy naturally present in sorghum–acha matrices. This finding contrasts with previous reports where fermentation improved FRAP values in cereal products, reinforcing that processing and formulation significantly influence antioxidant responses. The TEAC and ORAC assays further supported these observations. TEAC values ranged from 6.0 to 10.5 mmol TE/g, with SACPH showing the highest activity among the fortified blends, exceeding levels reported in polyphenol-enriched wheat bread [38]. ORAC values ranged from 18.2 to 22.2 μmol TE/g, reflecting strong peroxyl radical quenching capacity and surpassing levels seen in certain protein-derived antioxidant peptides [39]. Collectively, these data emphasize the antioxidant strength of cricket protein hydrolysate-enriched blends, particularly SACPH, for dietary oxidative stress modulation.

Beyond antioxidant properties, the study evaluated the blends’ inhibitory effects on α-amylase and α-glucosidase, enzymes critical to carbohydrate digestion and glucose absorption. Inhibiting these enzymes is a cornerstone of diabetes management, as it slows glucose release into the bloodstream, mitigating postprandial hyperglycemia [40]. The α-amylase inhibitory activity ranged from 38.5% (SOF) to 52.5% (SACPH), with cricket-extended samples significantly outperforming the control. This enhancement likely stems from bioactive peptides released during hydrolysis, which may bind to the enzyme’s active site or alter its conformation [41]. Compared to roasted sorghum or rice bran hydrolysates, the SACPH-extended blend’s higher inhibition suggests a potent antidiabetic potential [41]. Similarly, α-glucosidase inhibition ranged from 30.1% (SOF) to 46.0% (SACPH), exceeding values reported for malted millets [42]. The lack of significant difference between SAWCM and SADCM indicates that lipid content may not substantially affect inhibition, whereas hydrolysis markedly enhances it, possibly due to the increased solubility and enzyme-binding affinity of smaller peptides [43].

The in vivo antidiabetic efficacy of the fortified blends was evaluated using streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats, revealing significant reductions in fasting blood sugar levels across treated groups. SACPH demonstrated the most pronounced decline, especially within the first three weeks of feeding. This early glycemic improvement aligns with observations by Gribble FM, et al. [44] on insulin secretagogues and may result from the insulinotropic properties of cricket protein, which is rich in branched-chain amino acids such as leucine. Nguyen NQ, et al. [45] noted that leucine stimulates insulin secretion through mTOR pathway activation and glutamate dehydrogenase, enhancing glucose uptake. These findings echo the therapeutic benefits reported in high-protein dietary interventions, where a 30% protein intake significantly improved glycemic control in type 2 diabetic patients [46]. Additionally, the reversal of weight loss in diabetic rats fed cricket-enriched diets highlights the blends’ nutritional adequacy, likely driven by their high protein content (≥8%), which supports lean mass retention and appetite stimulation.

Lipid profile improvements were a significant outcome, with treated rats showing reductions in total cholesterol (TC), triglycerides (TG), and low-density lipoprotein (LDL), along with elevated high-density lipoprotein (HDL). This hypolipidemic effect, consistent with Vlachová M [47], suggests potential cardioprotective benefits for diabetic individuals, who are at heightened risk of cardiovascular complications. The presence of bioactive peptides and dietary fiber in the cricket-enriched blends may inhibit cholesterol absorption or synthesis [48], while antioxidant compounds contribute to reduced lipid peroxidation [49]. Compared to findings by Shahin (2017), who reported worsened lipid parameters in hypercholesterolemic rats, these blends demonstrated favorable modulation of serum lipids. Liver function markers, ALT, AST, and ALP, also improved, with levels approaching normal ranges as observed in Kalas MA, et al. [30]. This hepatoprotective effect is especially relevant, considering the liver's central role in glucose and lipid metabolism, often disrupted in diabetes. The antioxidant-rich blends likely attenuated hepatic stress and inflammation.

Serum total protein (TP) and albumin levels provided additional insights into metabolic health. Untreated diabetic rats exhibited elevated TP (7.43 g/dL) and albumin (5.83 g/dL), potentially reflecting dehydration or hepatic dysfunction [50]. In contrast, treated groups maintained levels within or approaching normal ranges (60–83 g/L for TP, 3.5–5 g/dL for albumin), indicating restored liver synthetic function and nutritional status [51]. These findings contrast with Akinsulie O, et al. [52], who reported higher TP and albumin in rats fed potato peels, highlighting the unique metabolic benefits of cricket-extended blends.

The implications of these results are multifaceted. The SACPH-extended blend’s superior antioxidant and enzyme inhibitory activities suggest that hydrolysis is a critical processing step for maximizing bioactivity, aligning with trends in functional food development [53]. The in vivo outcomes demonstrate practical efficacy, supporting the use of cricket protein as a sustainable, nutrient-dense ingredient in diabetes management. However, limitations must be addressed. The study’s reliance on an animal model necessitates human trials to validate these effects. The specific bioactive peptides driving these outcomes remain unidentified, requiring detailed characterization to elucidate mechanisms. Sensory and nutritional profiling of the blends is also essential for consumer acceptance, as their practical application hinges on palatability and marketability.

Future research should explore the integration of cricket-enriched sorghum–acha blends into widely consumed food products such as breads, snacks, or porridges, while assessing their long-term health impacts in human populations. Given their nutrient density, whole cricket derivatives could be incorporated into infant diets to support healthy weight gain, whereas defatted cricket meal may be more suitable for adults managing caloric intake. Additionally, cricket protein hydrolysates, due to their bioactive properties, could be formulated into specialized diets for managing metabolic diseases. These findings support the sustainable use of edible insects in targeted nutritional interventions across diverse age and health groups [54,55].

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, the sorghum-acha-cricket flour blends exhibit significant bioactive and antidiabetic properties, with SACPH standing out as a potent functional ingredient. By reducing oxidative stress, inhibiting carbohydrate-digesting enzymes, and improving metabolic markers in diabetic rats, these blends hold promise as a novel, sustainable approach to health promotion. The integration of traditional cereals with insect protein not only enhances nutritional value but also paves the way for innovative food solutions, bridging science, sustainability, and public health.

FUNDING STATEMENT

This research received no external funding and was entirely self-funded by the authors.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors sincerely appreciate the academic and technical support provided by the lecturers and staff of the Department of Food Science and Technology, Federal University of Agriculture, Makurdi, and the Federal University Dutsin-Ma, Katsina State.

REFERENCES

- Walia A, Gupta AK, Sharma V. (2019). Role of bioactive compounds in human health. Acta Sci Med Sci. 3(9):25-33.

- Samtiya M, Aluko RE, Dhewa T, Moreno-Rojas JM. (2021). Potential Health Benefits of Plant Food-Derived Bioactive Components: An Overview. Foods. 10(4):839.

- Zhou Y, Wang D, Zhou S, Duan H, Guo J, Yan W. (2022). Nutritional composition, health benefits, and application value of edible insects: A review. Foods. 11(24):3961.

- Owoicho MC, Idoko FA, Elijah AU-O.(2022). Energy optimization, proximate composition, minerals content and sensory evaluation of cookies: A comprehensive snack produced from defatted cricket. Int J Nutr Diet.8:25-33.

- Borges MM, da Costa DV, Trombete FM, Câmara AKFI. (2022). Edible insects as a sustainable alternative to food products: An insight into quality aspects of reformulated bakery and meat products. Current Opinion in Food Science. 46(80):100864.

- Hall F, Johnson PE, Liceaga A. (2018). Effect of enzymatic hydrolysis on bioactive properties and allergenicity of cricket (Gryllodes sigillatus) protein. Food Chem. 262:39-47.

- Salim ERA, El Aziz Ahmed WA, Mohamed MA, et al. (2017). Fortified Sorghum as a Potential for Food Security in Rural Areas by Adaptation of Technology and Innovation in Sudan. J Food Nutr Popul Health. 1:1.

- Mistry K, Sardar SD, Alim H, Patel N, Thakur M, Jabbarova D. (2022). Plant-based proteins: Sustainable alternatives. Plant Sci Today. 9(4):820-828.

- Ntui VO, Uyoh EA, Nakamura I, Mii M. (2017). Agrobacterium-mediated genetic transformation of Fonio (Digitaria exilis (L.) Stapf). Afr J Biotechnol. 16(23):1302-1307.

- Egbebi A, Muhammad A. (2016). Assessment of physico-chemical and phytochemical properties of white fonia (Digitaria exilis) flour. EPH-Int J Biol Pharm Sci. 2(1):1-8.

- Olagunju AI, Omoba OS, Enujiugha VN, Aluko RE. (2018). Development of value‐added nutritious crackers with high antidiabetic properties from blends of acha (Digitaria exilis) and blanched pigeon pea (Cajanus cajan). Food Sci Nutr. 6(7):1791-1802.

- Anyiam PN, Nwuke CP, Uhuo EN, Ije UE, Salvador EM, Mahumbi BM. (2023). Effect of fermentation time on nutritional, antinutritional factors and in-vitro protein digestibility of Macrotermes nigeriensis-cassava mahewu. Measurement: Food. 11(2023):100096.

- Sasidharan K. (2023). Translational genetics identifies a novel target to treat fatty liver disease.

- Temba MC, Njobeh PB, Adebo OA, Olugbile AO, Kayitesi E. (2016). The role of compositing cereals with legumes to alleviate protein-energy malnutrition in Africa. Int J Food Sci Technol. 51(3):543-554.

- Kamal RM, Abdull Razis AF, Mohd Sukri NS, Perimal EK, Ahmad H, Patrick R. (2022). Beneficial health effects of glucosinolates-derived isothiocyanates on cardiovascular and neurodegenerative diseases. Molecules. 27(3):624.

- Gat Y, Ananthanarayan L. (2015). Physicochemical, phytochemical and nutritional impact of fortified cereal-based extrudate snacks: effect of underutilized legume flour addition and extrusion cooking. Nutrafoods. 14(3):141-149.

- Marston K, Khouryieh H, Aramouni F. (2016). Effect of heat treatment of sorghum flour on the functional properties of gluten-free bread and cake. LWT-Food Sci Technol. 65:637-644.

- Ayo J, Adedeji O, Okpasu A. (2018). Effect of added moringa seed paste on the quality of acha-moringa flour blends. Asian Food Science Journal. 1(2):1-10.

- Agarwal JD, Agarwal A, Agarwal Y. (2017). Dynamics of Cricket and Cricket Derivatives. SSRN Electronic Journal. XXXI(4):1149-1189.

- Banwo K, Asogwa FC, Ogunremi OR, Adesulu-Dahunsi A, Sanni A. (2021). Nutritional profile and antioxidant capacities of fermented millet and sorghum gruels using lactic acid bacteria and yeasts. Food Biotechnology. 35(3):199-220.

- Girgih AT, Udenigwe CC, Aluko RE. (2011). In vitro antioxidant properties of hemp seed (Cannabis sativa L.) protein hydrolysate fractions. J Am Oil Chem Soc. 88(3):381-389.

- Benzie IF, Devaki M. (2018). The ferric reducing/antioxidant power (FRAP) assay for non‐enzymatic antioxidant capacity: concepts, procedures, limitations and applications. In: Measurement of Antioxidant Activity & Capacity: Recent Trends and Applications. pp. 77-106.

- Xie Z, Huang J, Xu X, Jin Z. (2008). Antioxidant activity of peptides isolated from alfalfa leaf protein hydrolysate. Food Chem. 111(2):370-376.

- Asma U, Bertotti ML, Zamai S, Arnold M, Amorati R, Scampicchio M. (2024). A kinetic approach to oxygen radical absorbance capacity (ORAC): Restoring order to the antioxidant activity of hydroxycinnamic acids and fruit juices. Antioxidants (Basel). 13(2):222.

- Cayres CA, Ascheri JLR, Couto MAPG, Almeida EL. (2021). Impact of pregelatinized composite flour on nutritional and functional properties of gluten-free cereal-based cake premixes. J Food Meas Charact. 15:769-781.

- Awosika TO, Aluko RE. (2019). Inhibition of the in vitro activities of α‐amylase, α‐glucosidase and pancreatic lipase by yellow field pea (Pisum sativum L.) protein hydrolysates. International Journal of Food Science & Technology. 54(6):2021-2034.

- Ochelle PO. (2025), Functional properties, proximate composition, and sensory of maize ogi enriched with African yam bean (Sphenostylis stenocarpa), soybean flours (Glycine max), and their protein isolates. Nutraceuticals Res. 4(2):15.

- Oyeleye SI, Olasehinde TA, Ademosun AO, Akinyemi AJ, Oboh G. (2019). Horseradish (Moringa oleifera) seed and leaf inclusive diets modulate activities of enzymes linked with hypertension and lipid metabolites in high-fat-fed rats. PharmaNutr. 7:100141.

- Oboh G, Oyeleye SI, Akintemi OA, Olasehinde TA. (2018). Moringa oleifera supplemented diet modulates nootropic-related biomolecules in the brain of STZ-induced diabetic rats treated with acarbose. Metab Brain Dis. 33(2):457-466.

- Kalas MA, Chavez L, Leon M, Taweesedt PT, Surani S. (2021). Abnormal liver enzymes: A review for clinicians. World J Hepatol. 13(11):1688-1698.

- Engwa GA, EnNwekegwa FN, Nkeh-Chungag BN. (2022). Free Radicals, Oxidative Stress-Related Diseases and Antioxidant Supplementation. Altern Ther Health Med. 28(1):114-128.

- Hassan MA, Xavier M, Gupta S, Nayak BB, Balange AK. (2019). Antioxidant properties and instrumental quality characteristics of spray dried Pangasius visceral protein hydrolysate prepared by chemical and enzymatic methods. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int. 26(9):8875-8884.

- Chen J, Liu Y, Zhao Z, Qiu J. (2021). Oxidative stress in the skin: Impact and related protection. Int J Cosmet Sci. 43(5):495-509.

- Kurutas EB. (2015). The importance of antioxidants which play the role in cellular response against oxidative/nitrosative stress: current state. Nutr J. 15(1):1-22.

- Gharibzahedi SMT, Smith B, Altintas Z. Bioactive and health-promoting properties of enzymatic hydrolysates of legume proteins: a review. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2024;64(9):2548-2578.

- Esfandi R, Walters ME, Tsopmo A. (2019). Antioxidant properties and potential mechanisms of hydrolyzed proteins and peptides from cereals. Heliyon. 5(4):e01538.

- Collin F. (2019). Chemical basis of reactive oxygen species reactivity and involvement in neurodegenerative diseases. Int J Mol Sci. 20(10):2407.

- Dziki D, Różyło R, Gawlik-Dziki U, Świeca M. (2014). Current trends in the enhancement of antioxidant activity of wheat bread by the addition of plant materials rich in phenolic compounds. Trends Food Sci Technol. 40(1):48-61.

- Du Y, Esfandi R, Willmore WG, Tsopmo A. (2016). Antioxidant activity of oat proteins derived peptides in stressed hepatic HepG2 cells. Antioxidants. 5(4):39.

- Mohamed SM, Shalaby MA, Al-Mokaddem AK, El-Banna AH, El-Banna HA, Nabil G. (2023). Evaluation of anti-Alzheimer activity of Echinacea purpurea extracts in aluminum chloride-induced neurotoxicity in rat model. J Chem Neuroanat. 128:102234.

- Uraipong C, Zhao J. (2016). Rice bran protein hydrolysates exhibit strong in vitro α‐amylase, β‐glucosidase and ACE‐inhibition activities. J Sci Food Agric. 96(4):1101-1111.

- Pradeep PM, Sreerama YN. (2015). Impact of processing on the phenolic profiles of small millets: evaluation of their antioxidant and enzyme inhibitory properties associated with hyperglycemia. Food Chem. 169:455-463.

- Kashtoh H, Baek K-H. (2022). Recent updates on phytoconstituent alpha-glucosidase inhibitors: An approach towards the treatment of type 2 diabetes. Plants. 11(20):2722.

- Gribble FM, Manley SE, Levy JC. (2001). Randomized dose ranging study of the reduction of fasting and postprandial glucose in type 2 diabetes by nateglinide (A-4166). Diabetes Care. 24(7):1221-1225.

- Nguyen NQ, Debreceni TL, Burgstad CM, Neo M, Bellon M, Wishart JM, et al. (2016). Effects of Fat and Protein Preloads on Pouch Emptying, Intestinal Transit, Glycaemia, Gut Hormones, Glucose Absorption, Blood Pressure and Gastrointestinal Symptoms After Roux-en-Y Gastric Bypass. Obes Surg. 26(1):77-84.

- Gannon MC, Nuttall FQ, Saeed A, Jordan K, Hoover H. (2003). An increase in dietary protein improves the blood glucose response in persons with type 2 diabetes. Am J Clin Nutr. 78(4):734-741.

- Vlachová M. (2016). Genetic determination of cholesterolemia regulation.

- Majdalawieh AF, Dalibalta S, Yousef SM. (2020). Effects of sesamin on fatty acid and cholesterol metabolism, macrophage cholesterol homeostasis and serum lipid profile: A comprehensive review. Eur J Pharmacol. 885:173417.

- del Hierro JN, Hernández-Ledesma B, Martin D. (2022). Potential of edible insects as a new source of bioactive compounds against metabolic syndrome. In: Current Advances for Development of Functional Foods Modulating Inflammation and Oxidative Stress. Elsevier. pp. 331-364.

- Malawadi B, Adiga U. (2016). Plasma proteins in type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Biotechnol Biochem. 2(5):1-3.

- Cameron JM, Bruno C, Parachalil DR, Baker MJ, Bonnier F, Butler HJ. (2020). Vibrational spectroscopic analysis and quantification of proteins in human blood plasma and serum. In: Vibrational Spectroscopy in Protein Research. Elsevier. pp. 269-314.

- Akinsulie O, Akinrinde A, Soetan K. (2021). Nutritional potentials and reproductive effects of Irish potato (Solanum tuberosum) peels on male Wistar rats. Nigerian Journal of Animal Production. 48(5):186-202.

- Nongonierma AB, Fitz Gerald RJ. (2019). Features of dipeptidyl peptidase IV (DPP‐IV) inhibitory peptides from dietary proteins. J Food Biochem. 43(1):e12451.

- Fan J, Yuan Z, Burley SK, Libutti SK, Zheng XS. (2022). Amino acids control blood glucose levels through mTOR signaling. Eur J Cell Biol. 101(3):151240.

- Yang J, Lee J. (2018). Korean consumers’ acceptability of commercial food products and usage of the 9‐point hedonic scale. J Sens Study. 33(6):e12467.

Abstract

Abstract  PDF

PDF

.png)

.png)