Current Issue

Functional Properties, Proximate Composition, and Sensory Evaluation of Maize Ogi Enriched with African Yam Bean (sphenostylis stenocarpa), Soybean Flours (Glycine max), and Their Protein Isolates

Ochelle Paul Ohini1,*, Kazeem Atanda Sogunle1, Onyenwe Innocentia Chidinma2

1Department of Food Science and Technology, Faculty of Renewable Natural Resources, Federal University, Dutsin-Ma, Katsina, Nigeria

2Department of Food Science and Technology, Joseph Sarwuan Tarka University, Nigeria

*Corresponding author: Ochelle Paul Ohini, Department of Food Science and Technology, Faculty of Renewable Natural Resources, Federal University, Dutsin-Ma, Katsina, Nigeria, Phone: 08029383858, E-mail: [email protected]

Received Date: October 02, 2025

Publication Date: November 12, 2025

Citation: Paul Ohini O, et al. (2025). Functional Properties, Proximate Composition, and Sensory Evaluation of Maize Ogi Enriched with African Yam Bean (sphenostylis stenocarpa), Soybean Flours (Glycine max), and Their Protein Isolates. Nutraceutical Res. 4(2):15.

Copyright: Paul Ohini O, et al. © (2025).

ABSTRACT

Background: Ogi, a traditional Nigeria fermented cereal gruel, is widely consumed but limited by low protein content. Enrichment with African Yam bean, soy flours, and their protein isolates has been shown to enhanced their quality attributes. Aim: This study evaluated the effect of African yam bean, soy flours, and their protein isolates addition on the functional properties, proximate composition, and sensory evaluation of maize ogi. Methods: Ogi was formulated to achieve 16% protein (dry weight) using material balance. The control (A) consisted of 100% maize flour, sample B (53.40% maize ogi: 46.60% African yam bean flour, sample C (76.40% maize ogi: 23.40% soy flour), sample D (89.40% maize ogi:10.60% African yam bean protein isolate), and Sample E (90.20% maize ogi: 9.80% soy protein isolate). Standard laboratory methods were used for analyses. Sensory evaluation employed a modified hedonic test (Ochelle, 2025) with 30 panellists. Results: Enrichment significantly (p<0.05) altered the functional and proximate properties of ogi. Protein isolates had higher foaming capacity (D: 16.01%; E: 21.02%) and oil absorption capacity (D: 1.51 ml/g; E: 1.71 ml/g) as compared to flour-enriched samples (B: 9.87%; C: 14.31% and 1.01, 1.22 ml/g, respectively). Protein content was highest in protein isolates enriched with ogi (D: 22.66%; E: 24.10%) relative to flour-enriched samples (B: 16.04 %; C: 19.65%). Sensory scores showed the control (A: 8.71) was most preferred, and all other samples were within an acceptable range of 6-9. Conclusion: Enrichment of maize ogi with African yam bean, soy flours, and their protein isolates significantly enhanced protein and functional properties while maintaining consumer acceptability.

Keywords: Malnutrition, African Yam Bean, Soybean, Functional Properties, Proximate Composition, Sensory Evaluation

INTRODUCTION

Ogi or pap is a local generic name for a fermented gruel or porridge made from cereals (commonly maize, sorghum, or millet). It is a staple food in most African countries [1]. It is also known as akamu and koko in eastern and northern Nigeria, respectively. It is commonly used as a complementary food for babies and young children and as a standard breakfast cereal for many homes. It is a smooth, free-flowing thin porridge obtained from wet-milled, fermented cereal grains, popularly served as a breakfast cereal and infant complementary food in Nigeria [2]. Ogi is produced from cereals such as sorghum, maize, and millet or their combinations [3]. A major disadvantage of cereal-based gruel, such as maize ogi, is its starchy nature, which causes it to absorb excessive water, resulting in a bulky gruel with decreased nutrient density [4]. Maize is a popular cereal that could be processed into starch and used as soup thickeners, pap (ogi), solid gel (eko), and mashed maize (egbo). It could also be processed into snacks like donkwa, popcorn, aadun, kokoro, and elebute [5]. It is a common food product that is eaten in the family of carbohydrates after rice and wheat; it can be eaten roasted or boiled [5,6]. Soybean, is a legume, is one of the nutritious and affordable sources of plant protein that has been employed to improve the diets of millions of people, especially low-income earners in developing countries, owing partly to its functional properties [7]. Soybeans contain proteins (40%), lipids (20%), minerals (5%), and B vitamins for human nutrition [8]. Processing is necessary to destroy or remove some of the undesirable constituents of legumes, such as to improve their palatability [9]. Compared to soybean, African yam bean is an underutilized legume indigenous to West and East Africa with nutritional content comparable to other commonly consumed legumes. The nutrient density of the crop makes it a viable food crop for ameliorating the challenges of malnutrition faced in many developing countries, via direct consumption or fortification and enrichment of less nutritious staples. African yam bean is a hard-to- cook underexploited leguminous plant grown extensively in Western Africa [10], Eastern and Central Africa [11]. Protein isolates are the most refined form of protein products containing the greatest concentration of protein (90 %) on a dry weight basis [12]. Its high concentration of protein, with the advantages of colour, flavour, and functional properties, makes it an ideal raw ingredient for use in beverages, infant and children's milk food, and certain types of specialty foods [12,13]. Protein isolates have been developed from a variety of legumes such as soybean, bambaranut, cowpea, peanut, canola, cashew nut, almonds, sesame, pinto, and navy beans [14]. A combination of flours and protein isolates from African yam bean and soybean with maize in ogi preparations led to nutritional enhancement of maize ogi. Malnutrition remains a critical issue in many developing countries, especially among children and low-income communities, where diets are often deficient in essential nutrients. Ogi, a popular cereal-based gruel in Nigeria, is commonly made from maize and other cereals, but its high starch content and low protein levels make it nutritionally inadequate [3]. Regular consumption of ogi as a staple food can lead to protein-energy malnutrition and deficiencies in essential amino acids, vitamins, and minerals [15]. Despite various efforts to fortify cereal-based foods, the lack of affordable, nutrient-dense options persists. Furthermore, while legumes like African yam bean and soybean, rich in bioactive peptides, are known for their high protein and nutrient content [16,17], they remain underutilized in traditional diets. There is a critical need to enhance the nutritional profile of ogi by incorporating these nutrient-rich ingredients. This research seeks to address the problem of malnutrition by developing and evaluating Ogi enriched with flours from African yam bean and soy flours and their protein isolates, and to assess the potential of this enriched product to provide a nutritionally balanced food source that can improve the dietary intake of vulnerable populations. Ogi, when prepared from maize and other cereal grains alone, is deficient in protein and could predispose high patronage communities (especially under-five children) to protein energy malnutrition. Processing of ogi (porridge) enriched with protein-rich legumes such as African yam bean, soybean, alongside their flours and protein isolates could combat malnutrition deficiency, while addressing significant health concerns. The broad objective of this work is the functional, proximate, and sensory evaluation of maize ogi enriched with flours and protein isolates from African yam bean and soybean.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

Maize (Zea mays), African yam bean (Sphenostylis stenocarpa), and soybean (Glycine max) were obtained from Wednesday Market, Dutsin-Ma, Kastina State. All equipment used was obtained from the Department of Food Science and Technology, Faculty of Renewable Natural Resources, Federal University, Dutsin-Ma, Katsina State.

Methods

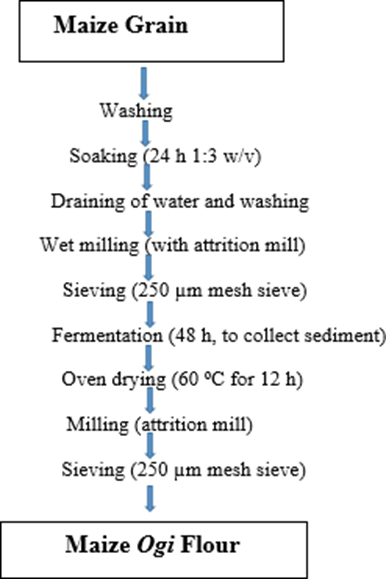

Preparation of maize Ogi

Ogi was processed according to the modified method of Chike and Onuoha [18] as shown in Figure 2. Maize grains were obtained, sorted to eliminate the bad grains, cleaned to remove debris and foreign materials, and steeped in clean tap water for 24 h at room temperature. The steeped grains were then washed with clean water, wet-milled using a commercial maize mill, and wet-sieved using a 250 μm sieve. The husks were disposed of while the filtrate (slurry) was allowed to ferment for 48 h. At the end of the fermentation period, the ogi was recovered by using a cheese cloth to squeeze out the water. The wet ogi sample was then dried in an oven (60 °C, 12 h). The dried starchy cake obtained was milled and sieved to obtain ogi flour.

Figure 1. Flow Diagram for the Processing of Maize Ogi.

Source: [18] modified.

Production of African Yam Bean Flour

African yam bean flour was prepared according to the modified method described by [19] as shown in (Figure 3). African yam bean was sorted to remove extraneous materials and damaged seeds. Soaked (10 h at 1:2 w/v), boiled for 30 min, dehulled manually (by rubbing in between the palms), and oven dried in the Gallenkamp (United Kingdom) moisture extraction oven at 60 °C for 12 h. The dried African yam bean was milled in a disc attrition mill into fine flour, followed by sieving through a 250µm mesh and packaging in airtight plastic containers, which were placed on shelves at room temperature until used.

Figure 2. Flow Chart for the Processing of African Yam Bean Flour.

Source: Igbokwe et al. [19].

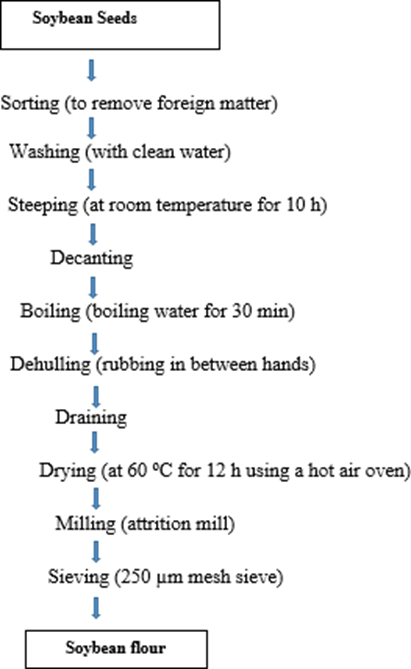

Production of Soybean Flour

Soybean flour was processed according to the modified method described by Bolarinwa et al. [20]. The soybean seeds were sorted to remove pebbles, stones, and other extraneous materials. They were wetted, cleaned, and steeped for 10 h. The steeped soybean seeds were drained and precooked for 15 min, followed by dehulling (by rubbing in between the palms), and the hulls were removed by rinsing with clean water. The dehulled soybean seeds were oven dried at 60 °C for 12 h and dry milled into fine flour. The soybean flour was sieved using a 250 μm mesh sieve to obtain smooth flour, as shown in Figure 3. The flour was defatted using n-hexane (flour to solvent ratio 1:5 w/v) as shown in Figure 5, with constant magnetic stirring provided for 4 hours. The trace of residual hexane was removed by placing the defatted flours inside a fume cupboard for 6 hours to dry. Flours obtained were packed in plastic tubes until further use.

Figure 3. Flow Chart for the Processing of Soybean Flour.

Source: Bolarinwa et al. [20].

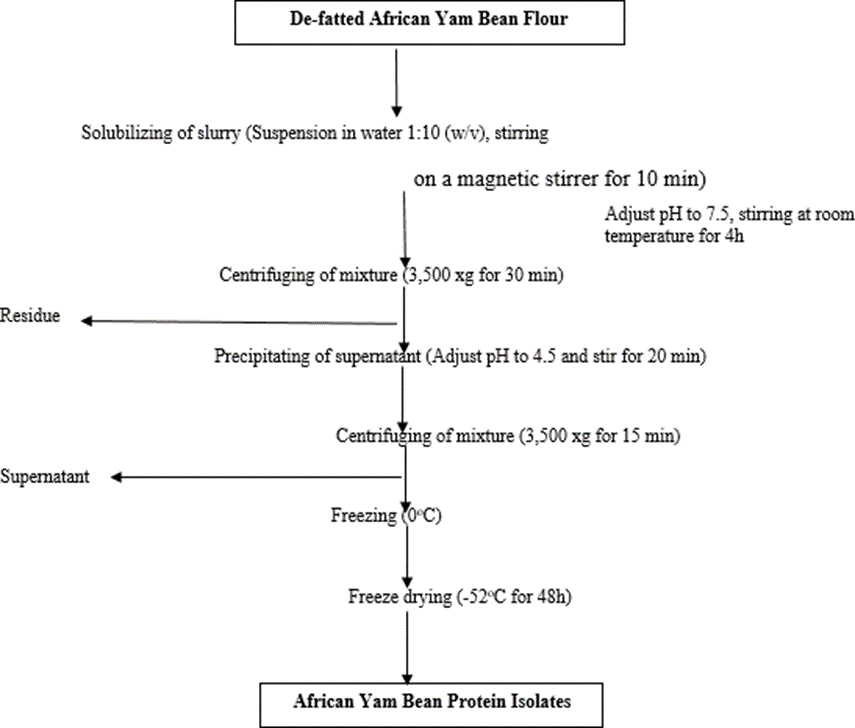

Processing of African Yam Bean Protein t Isolate

African yam bean protein isolates were extracted from defatted African yam bean flour using a modified isoelectric precipitation procedure as described by Gbadamosi et al. [21]. The defatted flour was dispersed in distilled water at a 1:10 (w:v) ratio. This was followed by an adjustment to pH 7.5 with 1.0 M NaOH to solubilize the protein. The resulting mixture was stirred using a magnetic stirrer for 4 h and centrifuged at 3,500 xg for 30 min. The residue was discarded, and the supernatant was filtered with cheesecloth and adjusted to pH 4.5 using 1.0 M HCl to precipitate most of the proteins. Thereafter, the mixture was centrifuged (3500 x g, 30 min). The resultant precipitate was redispersed in 25 ml of distilled water, frozen at 0 °C, and then freeze-dried at -52 °C to yield a free-flowing powder. The African yam bean protein isolates were stored in a sealed tube at 4 °C until analyzed. The flow chart for the processing of African yam bean protein isolates is shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4. Flow chart for the processing of African Yam Bean Protein Isolates.

Source: Gbadamosi et al. [21] modified.

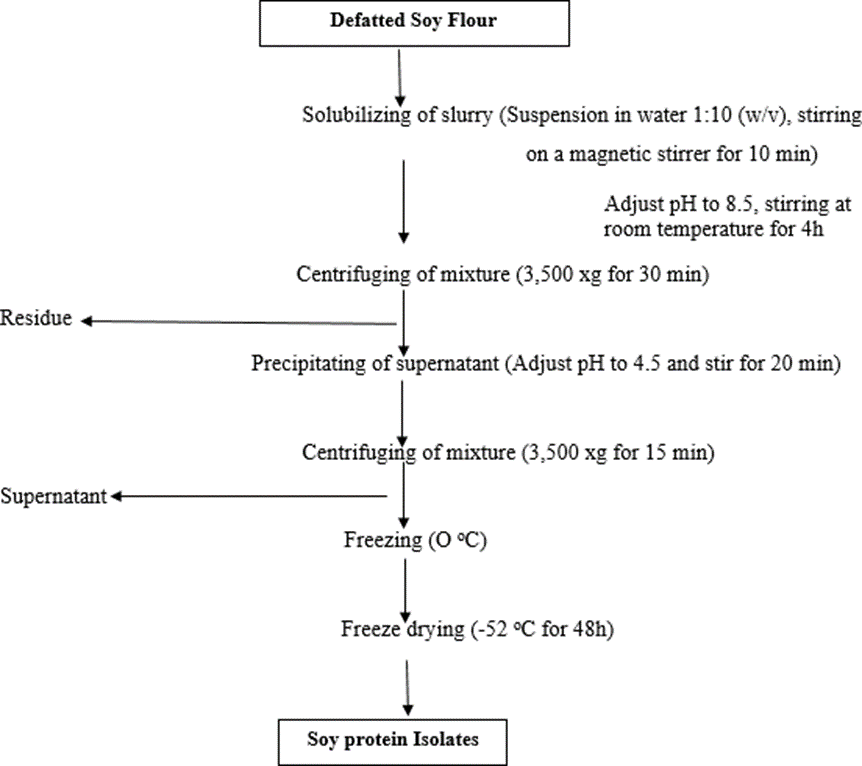

Processing of Soy Protein Isolate

Protein was extracted from defatted soy flour using a modified isoelectric precipitation procedure as described by Gbadamosi et al. [21]. The defatted flour was dispersed in distilled water at a 1:10 (w:v) ratio. This was followed by an adjustment to pH 8.5 with 1.0 M NaOH to solubilize the protein. The resulting mixture was stirred using a magnetic stirrer for 4 h and centrifuged at 3,500 xg for 30 min. The residue was discarded, and the supernatant was filtered with cheesecloth and adjusted to pH 4.5 using 1.0 M HCl to precipitate most of the proteins. Thereafter, the mixture was centrifuged (3500 x g, 30 min). The resultant precipitate was re-dispersed in 25 ml of distilled water, frozen at 0 °C, and then freeze-dried at -52 °C to yield a free-flowing powder. The soy protein isolate was stored in a sealed tube at 4 °C until analyzed. The flow chart for the processing of soy protein isolates is shown in Figure 5. The blend formulation is presented in Table 1.

Figure 5. Flow Chart for the Processing of Soy Protein Isolates.

Source: Gbadamosi et al. [21] modified.

Table 1. Blend Formulation to Achieve (16 %) Protein Content

|

Samples |

Maize Flour (MF) |

African Yam Bean (AYBF) |

Soybean Flour (SF) |

African Yam Bean Protein Isolate (AYBPI) |

Soy Protein Isolate (SPI) |

Total |

|

A |

100 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

100 |

|

B |

53.40 |

46.60 |

- |

- |

- |

100 |

|

C |

76.40 |

- |

23.60 |

- |

- |

100 |

|

D |

89.40 |

- |

|

10.60 |

- |

100 |

|

E |

90.20 |

- |

- |

- |

9.80 |

100 |

Functional Properties of Maize-Based Ogi Enriched with Flours and Protein Isolates from African Yam Bean and Soybean

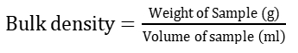

Bulk density (BD)

This was determined according to the method of Onwuka [22]. A ten millilitres capacity graduated cylinder was weighed on a digital balance. The cylinder was gently filled with the sample. The bottom of the cylinder was tapped on the laboratory bench several times until no further diminution of the sample level occurred after filling to the 10 ml mark.

Oil absorption capacity (OAC)

One gram of the sample was weighed into a 20 ml conical graduated centrifuge tube. Ten millilitres of vegetable oil of a known density (0.99 mg/ml) was added to the sample, and the mixture was stirred on a magnetic stirrer at 1000 rpm for 5 min. The mixture was centrifuged at 3500 rpm for 30 min, and the supernatant was removed and measured with a 10 ml measuring cylinder [22]. The OAC was calculated thus, Oil absorption capacity = volume of oil absorbed ×density×100/weight of sample used

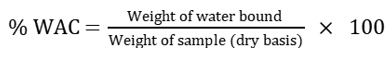

Water absorption capacity (WAC)

The water absorption capacity of the flour blends was determined as described by Onwuka [22]. One gram of the sample was weighed into a 20 ml conical graduated centrifuge tube. Using a warring whirl mixer, the sample was mixed thoroughly with 10ml of distilled water in a centrifuge tube for 30 minutes. The sample was allowed to stand for 30 minutes at room temperature and centrifuged at 500 rpm for 30 minutes. The volume of free water (the supernatant) was read directly from the graduated centrifuge tube.

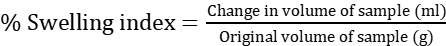

Swelling index

The swelling index was determined using the method of Onwuka [22]. Five grams’ portion (dry basis) of each sample was transferred into clean, dried graduated (50ml) cylinders. The samples were gently levelled and the volumes noted. Fifty millilitres of distilled water was added to each sample. The cylinder was swirled and allowed to stand for 60 minutes while the volume change (swelling) was recorded every 15minutes. The ratio of the initial volume to the final volume gave the swelling index.

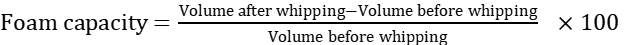

Foaming capacity

Foaming capacity was determined by the method of Onwuka [22]. One gram of each sample was blended with 50 mL of distilled water and whipped for 5 minutes at 1600 rpm. The whipped mixture was transferred into a 250ml measuring cylinder, and the volume was recorded after 30 seconds. Foam capacity was expressed as a percentage increase in volume using the formula below.

Gelatinization temperature

The gelatinization temperature was determined according to the method described by [22]. A suspension of 10 % of the sample in a test tube was prepared, and the aqueous suspension was heated in a boiling water bath with continuous stirring and was heated. The temperature 30 seconds after gelatinization was visually noticed as the gelatinization temperature and recorded.

Proximate Composition (%) of Maize Ogi Enriched with Flours and Protein Isolates from African Yam Bean and Soybean

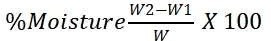

Determination of moisture content

The moisture content was determined by the hot air oven method as described by AOAC [24]. An empty crucible was weighed, and 2 g of the sample was transferred into the crucible. This was taken into the hot air oven and dried for 24 h at 100 °C. The loss in weight was regarded as the moisture content and expressed as:

Where:

W2=Weight of the crucible and dry Sample

W1=Weight of empty crucible

Weight of the Sample

Determination of Crude Protein Content

The microkjeldahl method, as described by AOAC [24], was used to determine the crude protein content of the maize ogi. Two grams of the sample were put into the digestion flask. The gramme of copper sulphate and sodium sulphate (catalyst) in the ratio 5:1, respectively, and 25ml concentrated sulphuric acid was added to the digestion flask. The flask was placed into the digestion block in the fume cupboard and heated until frothing ceased, giving a clear and light green colouration. The mixture was allowed to cool and diluted with distilled water until it reached 250 ml in a volumetric flask. The distillation apparatus was connected, and 10ml of the mixture was poured into the receiver of thedistillation apparatus. Also, 10ml of 40% sodium hydroxide was added. The released ammonia by boric acid was treated with 0.2 M of hydrochloric acid until the green colour changed to purple. The percentage of nitrogen in the sample was calculated using the formula:

Crude protein = % Total Nitrogen = (Titre blank) x Normality x N2. Nitrogen factor = 6.25.

Crude protein% % total Nitrogen X 6.25

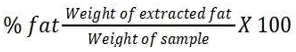

Determination of crude fat content

The Soxhlet extraction method described by AOAC [24] was used in determining the crude fat content of the samples. Two grams of the sample were weighed, and the weight of the flat-bottom flask was taken with the extractor. Mounted on it, the thimble was held halfway into the extractor, and the weight of the sample was applied. Extraction was carried out using a boiling point of 60 oC. The thimble was plugged with cotton wool. At completion of the extraction, which lasted for 8 hours, the solvent was removed by evaporation on a water bath, and the remaining part in the flask was dried at 80 oC for 30 minutes in the air oven to dry the fat, then cooled in a desiccator. The flask was reweighed and the percentage fat calculated thus:

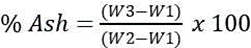

Determination of ash contents

The AOAC [24] method for determining ash content was used. Two grams of the sample were weighed into an ashing dish, which had been pre-heated, cooled in a desiccator, and weighed after reaching room temperature. The crucible and content were then heated in a muffle furnace at 550 °C for 6-7 h. The dish was cooled in a desiccator and weighed after reaching room temperature. The total ash was calculated as a percentage of the original sample weight.

Where:

W1 = Weight of empty crucible,

W2 = Weight of crucible + sample before ashing,

W3 = Weight of crucible + content after ashing.

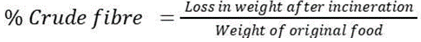

Determination of Crude Fiber Content

The method described by AOAC [24] was used for fibre determination. Two (2) grams of the sample were extracted using diethyl ether. This was digested and filtered through the California Buchner system. The resulting residue was dried at 130 ± 2 °C for 2h, cooled in a desiccator, and weighed. The residue was then transferred into a muffle furnace (Shanghai box type resistance furnace, No.: SX2-4-10N) and ignited at 550 °C for 30 min, cooled, and weighed. The percentage crude fibre content was calculated as:

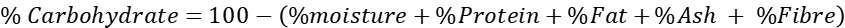

Determination of Carbohydrate Content

Carbohydrate content was determined by difference as follows:

Energy value (Kcal)

The caloric value (Kcal) was calculated by multiplying the mean of crude protein and total carbohydrate by the Atwater factor by 4 each, and that of crude fat multiplied by 9, and summing up the products as the energy value.

Sensory Properties of Maize Ogi Enriched with Flours and Protein Isolates from African Yam Bean and Soybean.

Sensory evaluation was conducted using the 9-point hedonic scale as described by Iwe [25], with modifications in the number of panellists. Unlike earlier works that employed 20 - 25 panellists, this study engaged thirty (30) panellists to improve precision and reliability. Maize ogi, which was neither too thin nor too thick, was prepared by mixing 40 g of each flour sample in 80 ml of hot water using a graduated plastic cup. Hot water was boiled using a cordless electric kettle (Sayona, model no. SCK-25). Maize ogi from the various flour blends was presented to a panel of 30 judges, including both students and members of staff of the Department of Food Science and Technology, Federal University, Dutsin-Ma, Katsina, Nigeria, to obtain a triad for sensory quality evaluation, chosen based on their familiarity and experience with maize ogi. Ogi produced from each flour blend, along with the reference sample, was presented in various coded forms and was randomly presented to the panellists. The panellists were provided with portable water to rinse their mouths between evaluations. However, a questionnaire describing the quality attributes (aroma, mouthfeel, taste, consistency, and overall acceptability) of the ogi samples was given to each panellist. A nine (9) point Hedonic scale as described by [25] was used with 1 and 9 representing dislike extremely and like extremely, respectively. 9 = Like extremely, 8 = Like very much, 7 = Like moderately, 6 = Like slightly, 5 = Neither like nor dislike, 4 = Dislike slightly, 3 = Dislike moderately, 2 = Dislike very much and 1 = dislike extremely.

Statistical Analysis of Samples

Data was subjected to analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Duncan’s Multiple Range Test to compare treatment means; differences were considered significant at 95% (P<0.05) (SPSS V21 software).

RESULTS

Functional Properties of the Individual Flours and Their Protein Isolates

The flours and protein isolates used in the formulation of maize-enriched ogi were characterized separately for their functional properties, as shown in Table 2. The bulk density, oil absorption capacity, water absorption capacity, and swelling index differed significantly (P<0.05). The bulk density ranged between 0.45 to 0.76 g/ml, the oil absorption capacity ranged from 1.00 to 1.43 ml/g, the water absorption capacity ranged between 1.00 and 1.59 ml/g, and the swelling index 1.01 and 1.75, respectively. The foaming capacity and gelatinization temperature ranged between 5.17 to 14.10 (%) and 49.99 to 70.50 °C, respectively.

Table 2. Characterization of Functional Properties of Maize Ogi, African yam bean flour, Soy flours, and Their Protein Isolates

|

Sample |

BD (g/ml) |

OAC (ml/g) |

WAC (ml/g) |

SI |

FC (%) |

GT (°C) |

|

Maize ogi |

0.76a±0.01 |

1.00e±0.03 |

1.59a±0.02 |

1.75a±0.02 |

5.17e±0.02 |

49.99e±0.02 |

|

African yam bean flour |

0.69b±0.02 |

1.06d±0.02 |

1.46b±0.02 |

1.33b±0.02 |

7.60d±0.02 |

56.39d±0.02 |

|

Soyflour |

0.57c±0.03 |

1.18c±0.02 |

1.30c±0.02 |

1.19c±0.02 |

8.88c±0.02 |

60.59c±0.02 |

|

African yam bean protein isolates (AYBPI) |

0.49d±0.02 |

1.31b±0.02 |

1.15d±0.02 |

1.10d±0.03 |

10.05b±0.02 |

68.04b±0.03 |

|

Soy Protein Isolates (SPI) |

0.45e±0.02 |

1.43a±0.02 |

1.00e±0.02 |

1.01e±0.02 |

14.10a±0.03 |

70.50a±0.02 |

Values are means ± standard deviations of triplicate determinations.

Means within the same column with different superscripts differed significantly (p<0.05)

BD Bulk Density, OAC Oil Absorption Capacity, WAC= Water Absorption Capacity, SI= Swelling Index, FC= Foaming Capacity, and GT= Gelatinization Temperature.

Proximate Composition of the Individual Flours and Their Protein Isolates

The flours and protein isolates used in the formulation of maize-enriched ogi were characterized separately for their proximate composition, as shown in Table 3. There were significant differences (P<0.05) in the moisture, crude protein, crude fat, crude ash, crude fiber, carbohydrate, and energy contents of the samples. The moisture content of maize ogi, African yam bean flour, soyflour, and their protein isolates were 10.20 %, 9.00%, 8.50%, 5.10% and 4.50 %, respectively. The crude protein content of maize ogi, African yam bean flour, soyflour, and their protein isolates were 9.00%, 24.00%, 38.65%, 74.70% and 80.10%, respectively. The crude fat content of maize ogi, African yam bean flour, soyflour, and their protein isolates were 4.50%, 2.80%, 19.00 %, 1.20 %, and 0.80 %, respectively. The ash contents were: 1.30 %, 3.33 %, 4.50%, 3.00 % and 2.90 %, respectively. The crude fiber content of maize ogi, African yam bean flour, soyflour, and their protein isolates was 2.20 %, 3.82 %, 3.03 %, 0.87 %, and 0.50 %, respectively. The carbohydrate content of maize ogi, African yam bean, soyflour, and their protein isolates were 72.80 %, 57.90%, 26.35%, 14.81 %, and 11.20%, respectively. Also, the energy value (Kcal) for the various flours: maize ogi, African yam bean flour, soyflour, and their protein isolates were; 367.70kcal, 352.80 kcal, 336.00 kcal, 370.03 kcal, and 372.40 kcal, respectively.

Table 3. Characterization of Proximate Composition of Maize Ogi, African yam bean, Soybean Flours, and their Protein Isolates

|

Samples |

Moisture content |

Protein |

Fat |

Fibre |

Ash |

CHO |

Energy |

|

Maize Ogi |

10.20a±0.02 |

9.00e±0.03 |

4.50b±0.8 |

2.20c±0.02 |

1.30d±0.01 |

72.80a±0.02 |

367.70c±0. 10 |

|

African yam bean flour |

9.00b±0.40 |

24.00d±0.51 |

2.80c±0.05 |

3.80a±0.05 |

3.22b±0.16 |

57.90b±0.04 |

352.80d±0.04 |

|

Soyflou R |

8.50c±0.03 |

38.65c±0.03 |

19.00a±0. 02 |

3.00b±0.12 |

4.50a±0.02 |

26.35c±0.02 |

336.00e±1.00 |

|

yam bean protein isolates |

5.10d±0.02 |

74.70b±0.49 |

1.20d±0.02 |

0.87d±0.06 |

3.03c±0.16 |

14.81d±0.02 |

370.03b±0.07 |

|

Soy protein isolates |

4.50e±0.02 |

80.10a±0.03 |

0.80e±0.02 |

0.50e±0.03 |

2.90c±0.02 |

11.20e±0.02 |

372.40a±0.02 |

Values are means ± standard deviations of triplicate determinations.

Means within the same column with different sperscripts differed significantly (p<0.05)

Functional, Proximate, and Sensory Evaluation of Maize Ogi Enriched with African yam bean Flour, Soyflour, and their Protein Isolates

Functional properties of maize ogi enriched with African yam bean flour, soyflours, and their protein isolates are presented in Table 4. The bulk density for the unfortified sample (100% maize ogi) and fortified samples were: 0.76, 0.69, 0.57, 0.49, and 0.45 (g/ml), respectively. Results were significantly influenced (P<0.05) by various substitution levels of flours and protein isolates from African yam bean flour and soyflour. Also, OAC, WAC, SI, FC, and GT were found to range significantly (P<0.05) between 1.01 to 1.71 (ml/g), 1.18 to 1.61 (ml/g), 1.28 to 1.78, 5.19 to 21. 02 (%) and 50.01 to 80.01 (°C), respectively.

Table 4. Functional Properties of Maize Ogi Enriched with African yam bean, Soy Flours, and their Protein Isolates

|

Sample |

BD (g/ml) |

OAC (ml/g) |

WAC (ml/g) |

SI |

FC (%) |

GT (°C) |

|

A |

0.81a±0.02 |

1.01e±0.03 |

1.61a±0.02 |

1.78a±0.03 |

5.19e±0.02 |

50.01e±0.02 |

|

B |

0.74b±0.01 |

1.22d±0.03 |

1.49b±0.01 |

1.57b±0.02 |

9.87d±0.02 |

60.00d±0.02 |

|

C |

0.66c±0.02 |

1.41c±0.02 |

1.37c±0.02 |

1.49c±0.02 |

14.31c±0.03 |

65.69c±0.50 |

|

D |

0.63c±0.02 |

1.51b±0.02 |

1.29d±0.03 |

1.33d±0.03 |

16.01b±0.03 |

72.55b±0.02 |

|

E |

0.59d±0.02 |

1.71a±0.02 |

1.18e±0.02 |

1.28e±0.03 |

21.02a±0.02 |

80.01a±0.03 |

Values are means ± standard deviations of triplicate determinations.

Means within the same column with different superscripts differed significantly (p<0.05)

Key: Sample A (100 % maize ogi), Sample B (53:40 maize ogi and 46.60 African yam bean flour), Sample C (76.40 maize ogi and 23.40 soy flour), Sample D (89.40 maize ogi and 10.60 African yam protein isolate), and Sample E (90.20 maize ogi and 9.80 soybean protein isolates).

The proximate composition (% dry weight) of maize ogi enriched with African yam bean flour, soyflours, and their protein isolates is depicted in Table 5. The moisture content, crude protein, and crude fat content of the composite flour ranged between 4.50 to 10.20 %, 9.17 to 24.10 %, and 0.80 to 4.50 % respectively. The ash, crude fiber, carbohydrate, and energy content of the samples ranged between 1.30 to 4.50 %, 0.50 to 3.82 %, 59.40 to 72.63 % and 350.62 to 372.64 kcal, respectively. Sensory properties of maize ogi enriched with African yam bean flour, soyflour, and their protein isolates are presented in Table 6. Sensory scores for aroma, appearance, taste, and consistency ranged between 7.30 and 8.44, 7.60 to 8.40, 7.78 to 8.81, and 7.50 to 8.15, respectively.

Table 5. Proximate Composition (% dry weight) of Maize Ogi Enriched with African yam bean, Soy Flours, and their Protein Isolates

|

Sample |

Moisture content |

Protein |

Fat |

Fibre |

Ash |

CHO |

Energy |

|

A |

10.20a±0.02 |

9.17e±0.07 |

4.50b±0.02 |

2.20c±0.02 |

1.30d±0.02 |

72.63a±0.08 |

367.70c±0.02 |

|

B |

9.04b±0.16 |

16.04d±0.03 |

2.81c±0.01 |

3.82a±0.06 |

3.33b±0.33 |

65.30c±0.01 |

350.62e±0.23 |

|

C |

8.50c±0.02 |

19.65c±0.03 |

4.92a±0.02 |

3.03b±0.07 |

4.50a±0.02 |

59.40d±0.07 |

360.47d±0.12 |

|

D |

5.10d±0.02 |

22.66b±0.57 |

1.20d±0.03 |

0.90d±0.03 |

3.00c±0.02 |

67.14b±0.52 |

370.12b±0.24 |

|

E |

4.50e±0.03 |

24.10a±0.03 |

0.80e±0.03 |

0.50e±0.03 |

2.90c±0.03 |

67.20b±0.15 |

372.64a±0.47 |

Values are means ± standard deviations of triplicate determinations.

Means within the same column with different superscripts differed significantly (p<0.05)

Key: Sample A (100 % maize ogi), Sample B (53:40 maize ogi and 46.60 African yam bean flour), Sample C (76.40 maize ogi and 23.40 soy flour) Sample D (89.40 maize ogi and 10.60 African yam protein isolate) and Sample E (90.20 maize ogi and 9.80 soybean protein isolates)

Sensory Scores of Maize Ogi Enriched with African yam bean flour, Soy flour, and their Protein Isolates

Sensory properties of maize ogi enriched with African yam bean flour, soy flour, and their protein isolates are presented in Table 6. Sensory scores for aroma, mouthfeel, taste, consistency, and overall acceptability ranged between 6.79 and 8.04, 7.55 to 8.20, 7.78 to 8.81, 7.50 to 8.15, 8.33 to 8.71, respectively.

Table 6. Sensory Evaluation of Maize Ogi Enriched with African yam bean, Soy Flours, and their Protein Isolates

|

Sample |

Aroma |

Mouth feel |

Taste |

Consistency |

Overall Acceptability |

|

A |

8.04a±0.01 |

8.20a±0.01 |

8.81a±0.01 |

7.50e±0.02 |

8.71a±0.02 |

|

B |

7.39b±0.02 |

8.00b±0.01 |

8.10b±0.02 |

7.71d±0.02 |

8.40b±0.02 |

|

C |

7.30c±0.02 |

7.85c±0.02 |

8.09b±0.02 |

7.91c±0.02 |

8.60c±0.02 |

|

D |

6.90d±0.02 |

7.70d±0.02 |

7.82c±0.02 |

8.10b±0.02 |

8.12d±0.02 |

|

E |

6.79e±0.02 |

7.55e±0.02 |

7.78d±0.02 |

8.15a±0.02 |

8.33e±0.02 |

Values are means ± standard deviations of triplicate determinations.

Means within the same column with different superscripts differed significantly (p<0.05).

Key: Sample A (100 % maize ogi), Sample B (53:40 maize ogi and 46.60 African yam bean flour), Sample C (76.40 maize ogi and 23.40 soy flour) Sample D (89.40 maize ogi and 10.60 African yam protein isolate) and Sample E (90.20 maize ogi and 9.80 soybean protein isolates).

DISCUSSION

Functional and Proximate Properties of the Individual Flours and Protein Isolates

Proximate assay is an important criterion used to assess the overall composition and nutritional status of any ingredient intended for food [26]. The proximate composition of maize ogi, and flours and protein isolates from African yam bean and soyflour showed a moisture content range of maize ogi (4.50 to10.20 %) observed to be significantly lower (p˂0.05) than the (7.85 to 14.91 %) reported by [27] who worked on the chemical composition, functional, and sensory properties of maize ogi fortified with periwinkle meat flour. Soy protein isolate had the highest crude protein content of 80.10 % similar to (89.31 %) for soy protein isolates reported by [28], who work on the quality and sensory properties of maize flour cookies enriched with soy protein isolate. The difference in value could be attributed to a varietal difference. Flours from African yam bean and soybean were found to be richer in fat, ash, and fiber when compared to their corresponding protein isolates. This could be as a result of the defatting process embarked upon isolation of protein. Also, the African yam bean and soy protein isolates had higher energy value when compared to their flour samples. The high energy value is of the essence since growing children need a lot of energy to support their growth. The values as well as extents of changes in functional properties of maize flour and flours from African yam bean and soybean were lower in most cases than in the protein isolates (Table 2). Adeyeye SAO, et al. [28] reported superior functionality for protein isolates compared to their respective flours. This might have been due to the concentration effects in moving from the multi-component flours to the isolated protein.

Functional Properties of Maize Ogi Enriched with African, Soy flours and their Protein Isolates

Bulk density results are used to evaluate the flour heaviness, handling requirement, and the type of packaging materials suitable for storage and transportation of food materials [29]. It indicates different packaging spaces and materials required for various food samples. Bulk density is a reflection of the load the samples can carry if allowed to rest directly on one another [3]. The bulk density of the maize ogi decreased with different incorporation levels of different levels of flours and protein isolates from African yam bean and soy flours. The bulk density of the 100 % maize ogi (0.81 g/ml) was higher than (0.60 g/ml) for maize ogi reported by Inyang and Effiong [27] but lower than (0.98) for maize ogi reported by [30]. It has been reported that bulk density is influenced by the structure of the starch polymers, and a loose structure of the starch polymers could result in low bulk density [31]. The observed decrease in bulk density with the addition of protein isolates, as observed in the protein isolates-enriched ogi (D and E) compared to those of flour-enriched ogi (B and C), could be a result of a reduction in carbohydrate content, which is known to influence bulk density [32]. The low bulk density observed in the flour and protein isolates enriched ogi is a good physical attribute in terms of transportation and storability [3]. Low bulk density is also important in infant feeding, where less bulk is desirable for their small stomach as it engenders consumption of more quantity of the lighter food items and consequently, more nutrients for the infants. In this study, the values for oil absorption capacity of the 100 % maize ogi increased with the enrichment of flours and protein isolates from African yam bean and soybean. This is in line with Inyang and Effiong [27], who recorded 0.75 ml/g for maize ogi increment with different incorporation levels of periwinkle meat flour. The higher oil absorption capacity recorded with ogi enriched with protein isolates in samples D and E over the control and flour samples could be attributed to the higher protein content and their hydrophobicity. Oil absorption capacity is a measure of the flavor-retaining capacity of flour, which is very important in food formulations [33]. Oil absorption capacity also measures the ability of food materials to absorb oil [34]. Nonpolar amino acids are known to enhance hydrophobicity, causing flours to absorb more oil [35]. Consequently, Ogi enriched with protein isolates has the potential to result in enhancement of flavor, improvement of palatability, and extension of shelf life of bakery or meat products, doughnuts, baked goods, porridges, pancakes, and soup mixes where fat absorption is desired. Oil absorption capacity is of great importance since fat acts as a flavor retainer and increases the mouth feel of foods [36]. The water absorption capacity of the samples decreased significantly (p˂0.05), with the addition of flours and protein isolates from African yam bean and soyflour. The water absorption capacity ranged from 1.18 to 1.61 ml/g. The water absorption capacity was highest for the control (sample A) and lowest for the maize ogi enriched with soy protein isolates (D and E). These results of these values are in agreement with the findings of Abioye et al. [37] and Ochelle et al. [38]. The higher water absorption capacity in the control sample could be attributed to its higher starch content. Jude-Ojei et al. [39] reported that flours with higher starch contents absorb a lot of water and swell rapidly as compared to food materials with less starch content. Water absorption capacity is the ability of a product to incorporate water, and water inhibition is an important functional trait in food such as sausages, custard, and dough [40]. It also refers to water retained by a food product following filtration and application of mild pressure of centrifugation [41]. Water absorption of flours is dependent mainly on the amount and nature of the hydrophilic constituents and, to some extent, on pH and the nature of the protein. It has been suggested that flours with high water absorption capacity, as seen in the control sample, could prevent staling by reducing moisture loss [38]. Result of the swelling capacity showed that all the samples differed significantly (p˂0.05) with the addition of flours and protein isolates from African yam bean and soybean. The value of the swelling capacity ranged from 1.02 to 1.75. The swelling capacity was highest for sample A (100% wheat flour) and lowest for sample E. This result agrees with [3]. A decrease in the swelling index could be due to weak bond forces with the addition of African yam bean and soybean flours and their isolates. The swelling capacity of flour granules indicates the extent of associative forces within the granule. Addition of flours and protein isolates to the maize ogi significantly (p˂0.05) improved the foaming capacity of the blends, ranging from 5.19 % in 100% maize ogi (A) to 21.02 % (E) for soy protein isolate-enriched ogi, owing to the higher protein content in the enriched blends. Brou et al. (2013) reported that foaming capacity is positively correlated with protein contents of food substances. Inyang and Effiong [27] opined that the ability of flours to generate foams depends on the presence of flexible protein molecules, which tend to decrease the surface tension of water. Foaming capacity is used to determine the ability of flour to foam, which is dependent on the presence of the flexible protein molecules that decrease the surface tension of water [42]. The higher foaming capacity of African yam bean and soy flour blends samples suggests that they may be good forming agents where forming is essential, such as in the beverage industries. Good foaming capacity is also desirable in the food system, where conferment of porosity is essential. The gelation temperature decreased significantly (p˂0.05) down the column with the addition of African yam bean and soybean flour; the value of the gelation temperature ranged from 49.99 to 70.50oC °C. Sample E had the lowest gelation temperature, while sample A had the highest gelation temperature. The results of these values are not in agreement with [43] who worked on the effect of acha and sprouted soybean flour addition on the quality of wheat based cookies but within the range of results of (50.63 -79.01) reported by [3], who worked on the quality evaluation maize based ogi enriched with flours and protein isolates from bambaranut and soybean flours with their isolates. Increasing fiber content appears to delay gelation and subsequently its temperature. Thus, higher heat energy is required to attain significant gelation. Gelling temperature might be associated with the relative ratio of amylase and amylopectin [44] in the composite flour.

Proximate Composition of Maize Ogi (% dry weight) Enriched with African yam bean, Soy Flour, and their Protein Isolates

The proximate composition of maize ogi enriched with flours from African yam bean, soybean, and their protein isolates is presented in Table 6. The moisture content of the maize ogi (control sample) and the fortified samples (B-D) differed significantly (p˂0.05). Moisture content of control sample (10.20 %) was significantly (p˂0.05) higher when compared with that of the composite samples. The moisture results of this study (4.50 to 10.20) are in agreement with the work of Ameh et al. [3] who reported a moisture content of (8.63-9.41 %) for maize ogi produced from bambaranut, soy flours, and their isolates but contrary to the moisture results of (18.56 to 30. 11 %) of wheat bread supplemented with water yam and soyflour reported by [38]. The value of the moisture content in this study is below the 14 % recommended by Amah et al. [45]. High moisture contents exceeding 14 % in flours encourage microbial activity and pose undesirable changes. The protein content of the maize ogi and fortified diets showed significant differences (p<0.05) among all samples. The protein isolates enriched ogi (D and E) had the highest value of protein content (22.66 to 24.10 %), and the control sample had the lowest protein content of 11.23 %. The protein contents were comparable with the values of 8.06 -31.36 % reported by Adeyeye et al. [6] for maize flour cookies enriched with soy protein isolate. The higher protein contents in the protein isolates enriched ogi as compared to the flour and control samples may be attributed to the higher protein contents of the isolates from African yam bean and soybean. This is evidenced by the nutritional composition of their individual flours (Table 1). The lower protein content of the control sample may be because it was processed from 100 % maize ogi. Also, the protein contents of the fortified diets meet the specification of 16 % and above recommended by [46-48] for complementary foods. The variations in reported values of protein contents could be due to differences in the varieties of flours used, growing conditions, as well as fermentation conditions. The higher protein contents in the isolates and flour samples would be useful in eliminating the challenges of protein deficiencies, notably among children under five [49,50]. Proteins are essential for all body tissues, which help to produce new tissues. They are therefore extremely important for growth, pregnancy, and when recovering from wounds [51]. The fat content of the protein isolates and flour samples showed significant differences (p<0.05). The flour-enriched ogi had higher (2.81 and 4.91 %) fat contents, while the protein-isolate-enriched ogi had lower fat contents of (1.20 and 0.80 %), respectively. The fat contents of the fortified and unfortified ogi in this present study are lower than those of (10.37 to 18.01 %) reported by Akoja and Ogunsina [52] for composite of maize based snacks (kokoro) fortified with pigeon pea concentrate but higher than those of (0.59 and 1.58 %) reported by Adeyeye et al. [6] for composite cookies from maize and soy protein isolates. The high fat contents of the flour-enriched ogi (C) as compared to the control and protein isolates samples may be due to the addition of soybean flour to the flour-enriched ogi (C), soybean being an oilseed has more oil in it compared to the other flours used for supplementing the other samples. Soybeans have been reported to contain appreciable amounts of minerals and fat [3,53]. Also, the lower fat contents in the protein isolate-enriched ogi samples are not unexpected; this is due to the defatting and precipitation processes embarked upon in isolating proteins from African yam bean and soybean used in substituting maize ogi in those blends. However, the results of the fat contents in this study fall within the value of not more than 10 % crude fat recommended by the Protein Advisory Group [46], implying that complementary foods formulated from any of the fortified blends will be capable of meeting the fat needs of the consumers. The ash content of food material could be used as an index of mineral constituents of the food because ash is the inorganic residue remaining after water and organic matter have been removed by heating in the presence of an oxidizing agent [54]. Hence, the samples with high percentage ash contents, as noticed in the flour-enriched ogi (B and C), are expected to have high concentrations of various mineral elements. The higher ash content of the flour-enriched ogi (C) observed could be attributed to the inclusion of soybean in the blends; this implied that the substituted soybean flour contained higher mineral elements than the flours used in substituting the other samples. Both the protein isolates and flour samples met the recommended dietary allowance (RDA) for ash in foods for children, ≤ 5.0 mg/100g, specified by [48,56]. The carbohydrate content of the samples decreased significantly (p<0.05) with the addition of flours and protein isolates from African yam bean and soybean. The carbohydrate content of the maize ogi ranged from 59.40 to 72.63 %. The control sample (sample A) had the highest carbohydrate content of (72.63 %) while the maize ogi enriched with soy flour sample (sample C) had the least carbohydrate content of (59.40 %). The carbohydrate content of both the control and fortified samples was greater than the minimum carbohydrate requirement 37% recommended by regulatory standards in Nigeria [57]. The lower carbohydrate contents in the fortified samples may be attributed to substitution effects. The calories of the fortified and control samples (350.62, 360.47, 370.12, 372.64, and 367.70Kcal) are within the specific minimum requirement of 380-425 kcal as recommended by FAO [58]. Tizazu et al. [59] also reported energy values of sorghum-based complementary food as 405.8 – 413.2 Kcal/100g, which is higher than the value obtained in this study. The calories in an infant's diet are provided by protein, fat, and carbohydrate, which are major components of complementary foods that help to meet the energy requirements of growing infants, and a lack of any of these leads to malnutrition [60]. Higher energy value of the protein isolate enriched ogi could find application in infant formula since growing children require high energy for growth. Ohizua et al. [34] pointed out that high energy content may be advantageous for the formulation of breakfast cereal and complementary foods. The human body requires energy for all bodily functions, including work and other activities, the maintenance of body temperature, and the continuous action of the heart and lungs. Energy is needed for the breakdown, repair, and building of tissues as well as essential for the growth of children [61].

Sensory Properties of Maize Ogi Enriched with African yam bean, Soy flours, and Their Protein Isolates

Sensory evaluation is usually carried out towards the end of product development or formulation cycle, and this is done to assess the reactions of consumers about the product in order to determine the acceptability of such a product. It is also an important criterion for assessing quality in the development of new products and for meeting consumer requirements [62]. The sensory characteristics of a food product are of paramount importance as they play an important role in determining the final product acceptability by consumers. Industries and food developers have embraced sensory evaluation as an invaluable tool for creating successful products and understanding the sensory properties of materials. The sensory attributes evaluated in this research include aroma, mouthfeel, taste, consistency, and overall acceptability. For aroma, the control sample (100 %) maize ogi was rated highest followed (8.04 followed by the flour samples B and C (7.39 and 7.30), respectively. Significant differences existed among samples. The lower aroma value observed in the protein isolates enriched ogi (D:6:90 and E: 6.79) as compared to the other samples may be attributed to the consumers' unfamiliarity with protein isolates. The panellist's preference for the control sample (A) over the other formulations may be due to their familiarity with maize ogi. Aroma is an important parameter of food [25]. Good aroma from food excites the taste buds, making the system ready to accept the product. Poor aroma may cause outright rejection of food before they are tasted. The aroma ratings of the evaluated samples are within acceptable limits and therefore would not be objectionable to the consumers, but could be further improved by adjusting processing conditions. The result of the mouth feel showed, the samples were significantly influenced (p<0.05) among samples by the addition of flours and protein isolates from African yam bean and soybean. However, the Sample (A) control sample was rated highest among other samples by the panelists; this may be attributed to their familiarity with maize ogi. The taste of the maize ogi decreased with the addition of flours and protein isolates from African yam bean and soybean. The scores for taste ranged between 8.81 to 7.78. Taste is the sweet sensation caused in the mouth by contact with a sweetening agent, and it is an important sensory attribute of any food. Ogi (porridge) of samples A (100 % maize ogi) and flour samples (B:8:10, C:8:09) had the highest taste. Differences in taste could be attributed to molecular changes in the flour due to different processing conditions (soaking, dehulling, drying, and defatting) that the raw materials were subjected to. The consistency results of ogi produced from (100 % maize flour), flours, and protein isolates from African yam bean and soybean revealed that the control sample A had the least rating of 7.50, followed by the flour sample of maize ogi and African yam bean flour (B: 7.71). The differences in the consistency rating of sample A as compared to others may be due to constitutional variations. This consistency is very important, as it determines the amount of food an individual can swallow, because consumers prefer a smooth gruel and not a coarse product. However, consistency of both the control and composite diets was within acceptable limits. Water absorption capacity and swelling index are important parameters that determine the consistency of the flour. A very thick consistency would need increased efforts to swallow and, therefore, may limit the food intake in young children who have not fully developed their swallow ability [63]. The sensory scores for overall acceptability of the porridge samples ranged between 8.12 and 8.71. There were significant (p<0.05) differences among the samples. Sample C had the highest mean score of 8.60, followed by the African yam bean flour enriched sample (B: 8:40), respectively. Also the appearance results showed significant (p<0.05) difference among samples with sample A (control) having the highest score of (7.69) and the soy protein enriched protein isolates sample having the least appearance score of (7.00), the penallists preference for sample A (control) over the other samples maybe due to their familiarity with maize ogi. A good appearance makes a food product more appealing and attracts consumers to buy it. All the sensory scores evaluated were more than the minimum acceptable score of six (6) [64]. The results revealed high mean scores in all the sensory attributes evaluated, as all the samples maintained a high level of acceptability by the panelists, suggesting that acceptable protein-enriched ogi could be made from maize flour and either African yam bean or soy flour, as well as their protein isolates.

CONCLUSION

The study investigated the effect of the addition of flours and protein isolates from African yam bean and Soyflour with maize ogi on the functional, proximate composition, and sensory attributes of five porridge formulations, and the following conclusions were drawn. Functional properties of the maize ogi flour were altered significantly by the addition of legume flours and protein isolates from African yam bean and soybean. The protein composition of the maize ogi was enriched significantly by the addition of the legume flours and protein isolates from both African yam bean and soybean. The higher protein following the enrichment of maize ogi with the legume flours and protein isolates will help in alleviating protein-energy malnutrition. The protein isolates enriched ogi conferred higher foaming capacity, oil absorption capacity. The maize ogi enriched with African yam bean and soyflour and their protein isolates did result in acceptable sensory scores. It is recommended that maize ogi be enriched with either flour or protein isolates from African yam bean or soyflour to help in improved protein delivery, particularly in a resource-constrained environment.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

None.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- Omah EC, Nwaudah EL, Asogwa IS, Eze CR. (2011). Quality Evaluation of Powered Ogi from Maize, Sorghum, and Soybean Flour Blends in Nigeria. African Journal of Agricultural Science and Development. 21(10):18839-18854.

- Darlinton O. (2015). How to start custard powder production and the recipes. Constative. Available at: http://constative.com/news/how-to-start-custardpowderproductionand-the-recipe

- Ameh CO, Abu JO, Bunde-Tsegba EM. (2023). Chemical and Sensory Properties of Maize Ogi Enriched with Flours and Protein Isolates from Bambaranut and Soybean. Applied Sciences Research Periodicals. 1(9):33-60.

- Adepeju AB, Aladesiun OA, Oyinloye AM, Olugbuyi AO, Oni K. (2024). Spice fortification of “ogi” from maize, millet, and sorghum blend. FUOYE Journal of Pure and Applied Sciences. 9(2):93-101.

- Olanipekun OT, Olapade OA, Sauleiman P, Ojo SO. (2015). Nutrient and Sensory Analysis of Abari made from a Composite of Kidney Bean Flour and Maize Flour. Sky Journal of Food Science. 4(2):019-023.

- Adeyeye SAO, Adebato-Oyetero AO, Ominiyi SA. (2017). Quality and Sensory Properties of Maize Flour Cookies Enriched with Soy Protein Isolate. Cogent Food and Agriculture. 3:1278827.

- Iwe MO. (2023). Science and Technology of Soybean. Enugu: Rejoint Communication Services Ltd. pp. 324-342.

- Lee GJ, Wu X, Shannon GJ, Sleper AD, Nguyen TH. (2007). Soybean, Genome Mapping and Molecular Breeding in Plants. In: Kole C, editor. Oilseeds. Berlin/Heidelberg: Springer. p. s1-s53.

- Amoikon KE, Esse SE, Kouame KJ, Kati-Coulibaly SS. (2023). Cultural and Socio-Economic Factors and Risk of Protein-Energy Malnutrition in Children from 0 to 59 Months Attending the General Hospital of Bingerville (Côte d’Ivoire). International Journal of Current Research. 15(1):123-130.

- Zhang Y, Wang L, Li D, Chen F. (2024). Chromosome-scale assembly of the African yam bean genome. Scientific Data. 11:210.

- Liu X, Zhang Y, Li D, Chen F. (2024). Serological and RT-PCR Evaluation of African Yam bean Accessions for Resistance to Viral Infection. Scientific Reports. 14:59977.

- Khushairay ESI, Ghani MA, Babji AS, Yusop SM. (2023). The Nutritional and Functional Properties of Protein Isolates from Defatted Chia Flour Using Different Extraction pH. Foods. 12(16):3046.

- Fasolin LH, Pereira RN, Pinheiro AC, Martins JT, Andrade CCP, Ramos OL, et al. (2019). Emergent food proteins - Towards sustainability, health and innovation. Food Res Int. 125:108586.

- Ashfaq F, Butt MS, Suleria HAR, Khalid N. (2021). A Comprehensive Review on Protein Isolates from Legumes: Characterization, Functional Properties, and Health Perspectives. Legume Science. 3(1):e126.

- WHO. (2009). Infant and Young Child Feeding. Model Chapter for Textbooks for Medical Students and Allied Health Professionals. Geneva: World Health Organization.

- Teniola OD. (2021). Selection, use, and the influence of starter cultures in the nutrition and processing improvement of Ogi. Food Science and Nutrition Technology. 6 (1):1-10.

- Hew MQ, Lim C, Gooi HH, Ee KY. (2024). Integrating in Silico Analysis and Submerged Fermentation to Liberate Antioxidant Peptides from Soy Sauce Cake with Halophilic Virgibacillus sp. CD6. Journal of Food Science and Technology. 1(2):115-120.

- Chike TE, Onuoha AB. (2016). Nutrient Composition of Cereal (Maize), Legume (Soybean), and Fruit (Banana) as a Complementary Food for Older Infants and Their Sensory Assessment. Journal of Food Science and Engineering. 6(2):139-148.

- Igbokwe QN, Okoye JI, Egbujie AE. (2024). Effect of Thermal Processing Treatments on the Proximate, Functional, and Pasting Properties of African Yam Bean (Sphenostylis stenocarpa) seed flours. Asian Journal of Food Research and Nutrition. 3(2):329-342.

- Babarinde G, Adeyanju J, Omogunsoye A. (2019). Protein-enriched breakfast Meal from Sweet Potato and African Yam Bean Mixes. Bangladesh Journal of Science and Industrial Research. 54(2):125-130.

- Gbadamosi SO, Abiose SH, Aluko RE. (2012). Amino Acid Profile, Protein Digestibility, Thermal and Functional Properties Conophor Nut (Tetracarpidium conophorum) Defatted Flour, Protein Concentrate, and Isolates. International Journal of Food Science and Technology. 47(4):731-739.

- Onwuka GI. (2005). Food analysis and instrumentation: theory and practice. 1st ed. Lagos: Naphthali Prints.

- Nwosu JN. (2014). Evaluation of the Proximate Composition and Antinutritional Properties of African Yam Bean (Sphenostylis stenocarpa) Using Malting Treatment. International Journal of Basic and Applied Science Journal. 2:157-169.

- AOAC. (2012). Official Methods of Analysis. 19th ed. Washington, D.C.: Association of Official Analytical Chemists.

- Iwe MO. (2002). Handbook of Sensory Methods and Analysis. Enugu: Rejoint Communication Services Ltd..

- Qayyum MMN, Butt MS, Anjum FM, Nawaz H. (2012). Composition Analysis of Some Selected Legumes for Protein Isolates Recovery. Journal of Animal Plant Science. 22(4):1156-1162.

- Inyang UE, Effiong WE. (2016). Chemical Composition, Functional and Sensory Properties of Maize Ogi Fortified with Periwinkle Meat Flour. International Journal Nutrition and FoodSci. 5(3):195-200.

- Adeyeye SAO, Adebato-Oyetero AO, Ominiyi SA. (2017). Quality and Sensory Properties of Maize Flour Cookies Enriched with Soy Protein Isolate. Cogent Food Agricultural journal. 3:1278827.

- Oppong D, Arthur E, Kwadwo SO, Badu E, Sakyi P. (2015). Proximate Composition and Some Functional Properties of Soft Wheat Flour. International Journal of Innovation Research Science and Engineering Technology. 4(2):753-758.

- Asouzu AI, Umerah NN. (2020). Rheology and Acceptance of Pap (Zea mays) Enriched with Jatropha carcus Leaves to Improve Iron Status in Children. Asian Journal of Biochemisty and Genetic Molecular Biology. 3(2):22-34.

- Malomo O, Ogunmoyela OAB, Adekoyeni OO, Jimoh O, Oluwajoba SO, Sobanwa MO. (2012). Rheological and Functional Properties of Soy-poundo Yam Flour. International Journal of Food Science, Nutrition, and Engineering. 2(6):101-107.

- Gernah DI, Ariahu CC, Ingbian EK. (2011). Effects of Malting and Lactic Fermentation on Some Chemical and Functional Properties of Maize. American Journal of Food Technology. 6:404-412.

- Ajatta MA, Akinola SA, Osundahunsi OF. (2016). Proximate, Functional, and Pasting Properties of Composite Flours Made from Wheat, Breadfruit, and Cassava Starch. Journal of Applied Tropical Agriculture. 21(3):158-165.

- Ohizua ER, Adeola AA, Idowu MA, Sobukola OP, Afolabi TA, Ishola RO, et al. (2017). Nutrient composition, functional, and pasting properties of unripe cooking banana, pigeon pea, and sweetpotato flour blends. Food Sci Nutr. 5(3):750-762.

- Oluwalana IB, Oluwamukomi MO, Fagbemi TN, Oluwafemi GI. (2011). Effects of Temperature and Period of Blanching on the Pasting and Functional Properties of Plantain (Musa parasidiaca) Flour. Journal of Stored Prod Postharvest Research. 2(8):164-169.

- Bolaji OT, Oyewo AO, Adepoju PA. (2014). Soaking and Drying Effect on the Functional Properties of Ogi Produced from Some Selected Maize Varieties. American Journal of Food Science and Technology. 2(5):150-157.

- Abioye V, Olanipekun B, Omotosho O. (2015). Effect of Varieties on the Proximate, Nutritional and Anti-Nutritional Composition of Nine Variants of African Yam Bean Seeds (Sphenostylis stenocarpa). Journal of Food Technology. 7(6):182-188.

- Ochelle PO, Ikya JK, Ameh CO. (2019). Quality Assessment of Bread from Wheat, Water Yam, and Soybean Flours. Asian Food Science Journal. 10(3):1-8.

- Jude-Ojei BSC, Lola A, Ajayi IO, Seun I. (2017). Functional and Pasting Properties of Maize Ogi Supplemented with Fermented Maize Seeds. J Food Process Techno. 8(5):674.

- Ojo MO, Ariahu CC, Chinma EC. (2017). Proximate, Functional, and Pasting Properties of Cassava Starch and Mushroom (Pleurotus pulmonarius) Flour Blends. American Journal of Food Science Technology. 5(1):11-18.

- Falade KO, Okafor CA. (2015). Physical, functional, and pasting properties of flours from corms of two Cocoyam (Colocasia esculenta and Xanthosoma sagittifolium) cultivars. J Food Sci Technol. 52(6):3440-3448.

- Asif-Ul-Alam SM, Islam MZ, Hoque MM, Monalis K. (2014). Effect of Drying on the Physicochemical and Functional Properties of Green Banana (Musa sapientum) Flour and Development of Baked Product. American Journal of Food Science and Technology. 2(2):128-133.

- Eke MO, Ahure D, Donaldben NS. (2018). Effect of Acha and Sprouted Soybean Flour on the Quality of Wheat-Based Cookies. Asian Food Science Journal. 7(2):1-12.

- Chakroborty I, Pooja-Mal SS, Paul UC. (2022). An Insight into the Gelatinization Properties Influencing the Modified Starches Used in the Food Industry: A Review. Food Bioprocess Technology. 15(6):1195-1223.

- Amah CA, Ezenwafor CE, Akpan JE. (2024). Quality Assessment of Pulverised Flour Blends of Banana (Musa sapientum) and Date Palm (Phoenix dactylifera). Ressearch Journal of Food Science and Quality Control. 10(5):81-98.

- Protein Advisory Group. (1971). Guidelines on Protein-Rich Mixtures for Use as Weaning Foods. United Nations. pp. 45-76.

- Muller O. (2005). Malnutrition and Health in Developing Countries. CMAJ. 173:279-286.

- FAO/WHO. (1998). Carbohydrates in Human Nutrition: Report of a Joint FAO/WHO Expert Consultation. FAO Food and Nutrition Paper No. 66. Rome.

- Atobatele OB, Afolabi MO. (2016). Chemical Composition and Sensory Evaluation of Cookies Baked from Blends of Soybean and Maize Flours. Applied Tropical Agriculture. 21(2):8-13.

- Yusufu MI, Ejeh DD. (2018). Production of Bambara Groundnut Substituted Whole Wheat Bread: Functional Properties and Quality Characteristics. Journal of Nutritional Food Science. 8(5):731.

- Adebowale YA, Schwarzenbolz U, Henle T. (2011). Protein Isolates from Bambara Groundnut (Voandzeia subterranean L.): Chemical Characterization and Functional Properties. International Journal of Food Propagation. 14(4):758-775.

- Akoja SS, Ogunsina TO. (2018). Chemical Composition, Functional and Sensory Qualities of Maize-Based Snacks (Kokoro) Fortified with Pigeon Pea Protein Concentrate. Journal of Environmental Science and Toxicological Food Technology. 12(9):42-49.

- Apotiola ZO, Fashakin JF. (2013). Evaluation of Cookies from Wheat, Yam, and Soybean Blends. Journal of Food Science and Quality Management. 14:222-229.

- Ukegbu PO, Anyika JU. (2012). Chemical Analysis and Nutrient Adequacy of Maize Gruel (pap) Supplemented with Other Food Sources in Ngor-Okpala LGA, Imo State, Nigeria. Biological, Agricultual and Health. 2(6):20-22.

- FAO/WHO. (1994). Fats and Oils in Human Nutrition: Report of a Joint Expert Consultation. FAO Food and Nutrition Paper No. 57. Rome.

- FSSAI. (2012). The Food Standards (Food Products and Food Additives) Regulations. New Delhi: Commercial Law Publishing.

- Standards Organization of Nigeria (SON). (2004). Standard on Whole Wheat Bread. NIS 470.

- FAO. (2004). Energy Requirements in Human Nutrition (2nd ed). Geneva.

- Tizazu SK, Urga C, Abuye P, Retta N. (2010). Improvement of Energy and Nutrient Density of Sorghum- Based Complementary Foods Using Germination. African Journal of Food Nutrition and Development. 10(8):1684-5358.

- Adeoti OA, Osundahunsi OF. (2017). Nutritional Characteristics of Maize-Based Complementary Food Enriched with Fermented and Germinated Moringa oleifera Seed Flour. International Journal Food Science, Nutrition, and Dietetics. 6(2):350-357.

- FAO. (2004). Energy Requirements in Human Nutrition (2nd ed). Geneva.

- Dogo SB, Doudjo S, Mohamed AY, Ernest KK. (2018). Physico-Chemical, Functional, and Sensory Properties of Composite Bread Prepared from Wheat and Defatted Cashew (Anacardium occidentale L.) Kernel Flour. International Journal of Environmental Agricultural Research. 4(4):88-98.

- Tiencheu B, Achidi AU, Fossi BT, Tenyang N, Ngongang EF, Womeni HM. (2016). Formulation and Nutritional Evaluation of Instant Weaning Foods Processed from Maize (Zea mays), Pawpaw (Carica papaya), Red Beans (Phaseolus vulgaris), and Mackerel Fish Meal (Scomber scombrus). American Journal of Food Science and Technology. 4(5):149-159.

- Ibidapo OP, Ogunji A, Akinwale T, Owolabi F, Akinyele O, Efuribe N. (2017). Development and Quality Evaluation of Carrot Powder and Cowpea Flour Enriched Biscuit. International Journal of Food Science Biotechnology. 2(3):67-72.

Abstract

Abstract  PDF

PDF